The Ultimate Ponzu Soy Sauce Recipe (究極のポン酢作り方)

Ponzu (ポン酢) derived from the dutch word ‘pons’ for punch (as in the drink you serve in a bowl at parties) somewhat accurately describes this citrusy and tangy dipping sauce used for hotpot and sashimi. In its purest form, you could easily argue that ponzu sauce is soy sauce added with any juice from a citrus fruit, while the other added elements like katsuobushi and kombu just provide additional savory notes to the sauce. This sauce is worthy of writing about as it plays on the harmony of all 5 tastes with the saltiness from the soy sauce, the sweetness from sugar and mirin, the bitterness from bitter citrus and citrus juice left to age, umami from the dried fish and kombu and sourness from the blend of citrus juice and vinegar.

The beginning of the rabbit hole journey when researching this recipe came when I stumbled across this extremely old website by a man named Frank Nyappa (a pseudonym of course) that started in 1998 (and is still active as of 2021) that only reviews ponzu sauces.

The website has absolutely no decorations or styling at all, and is one of those text only websites from way back in the day. Mr Nyappa has been diligently adding ponzu sauces reviews steadily and gradually since then and is now up to over 150 different brands. He ranks them in an extremely stringent and no nonsense manner in a 100 point scale, with those that he deems worth recommending to people being inducted into the ponzu “Hall of Fame”. He is also particular about testing procedures and believes that ponzu should be tested in combination with chinese cabbage, udon, enoki mushroom and pork in a hotpot.

The following is the website link: https://www.nyappa.com/ponzu/guide/guide.html

What caught my eye on this website the most however was that the ponzu sauce by the famous puffer fish restaurant in Osaka, Zuboraya (づぼらや) scored a whopping 98 points to crush all other competition. And this isn’t like wine scores which tend to give all wines a ranking over 90, or tripadvisor and yelp where everyone gives places 5/5 stars. If you’ve ever been to any Japanese ranking site, take for example the famous tabelog that ranks restaurants out of 5 stars, you know they use the entire 5 star ranking system, with restaurants being able to score in the low 2 stars-ish, and with restaurants with 4 stars and above typically being michelin starred restaurants or restaurants with at least a 1.5 hour queue out the door. In fact, his website even states: “定期的に相対比較で点数を見直し、定期的に「点数を下げて全体の調整を図る」ということを行っております。” which means that he regularly adjusts the scores so that they cover the range of points, so that as newer and better ponzu sauces are found, others can be knocked down a few points. So all in all, this guy is doing a pretty thorough job.

The reason why I was looking into all this was because I was looking to make a solid ponzu sauce recipe for my website and whilst we had a sauce we called ponzu at the restaurant I worked at, it was more of a quick mix of a couple of ingredients, rather than the traditional method of making ponzu sauce that required at least a month of aging. Upon further looking around, it turns out that the famous Zuboraya restaurant that has topped the rankings had sadly closed down permanently due to covid-19. This spurred me on to see if it would actually be possible to recreate Zuboraya’s ‘Hall of Fame’ ponzu sauce?

This is where a company called Asahi Foods (旭食品) comes into play. Based in Yao City (八尾市) in Osaka, the founder, Koji Takada (耕治悦司) back in 1984, was a frequent patron of the Zuboraya, but his company mainly manufactures soup stock and frozen goods. However, he was so blown away by the ponzu sauce at Zuboraya that he started to experiment with replicating it at his own company, going as far as to document his findings in several notebooks of which you can find pictures of on their website along with a bunch of other history. After several years of trial and error, Asahi Ponzu (旭ポン酢) was then released to the public and is now one of the most successful ponzu sauces on the market. His son, Etsuji Takada (高田悦司), now the current president of the company, even made a public statement upon the news that Zuboraya had now closed down permanently stating that if it weren’t for Zuboraya that inspired his father, their company’s most famous product, Asahi ponzu, would not exist.

The science behind making great ponzu sauce

When you delve into the world of ponzu sauces, there exists 3 main criteria for what constitutes a well made sauce. Firstly, the juice of the citrus fruits used are hand squeezed, or at the very least not squeezed with an electric machine (so using a wooden press is acceptable). I would argue that there does exist some science behind this based on Milind Ladaniya’s book: Citrus Fruit: Biology, Technology and Evaluation, through a process known as enzymatic bittering. Limonin, which is an easily tasted bitter chemical, and is not present in freshly squeezed citrus juice. However, as we squeeze the citrus fruit, enzymes are released into the juice that convert certain chemicals into limonin (thus the name enzymatic bittering), which explains why lemon or lime juice gradually becomes bitter over time. It seems however, that the majority of enzymes that cause this bittering is present in the pith and peel of citrus fruits, which is why over squeezing the citrus fruits, or using a machine that applies massive force to the fruit is not ideal when making ponzu sauce as you’re releasing more of the enzymes that cause bitterness.

Secondly, there is great emphasis that good ponzu sauce should be aged for at least a week and optimally a month or longer. Now there’s already plenty of writing out there on why ageing various foods make them taste better, from wine to miso to soy sauce etc, and this would be the perfect opportunity to use the term ‘maillard reaction’. However, I do not like this term as I feel it is extremely overused but if you’d like to find out more, the information is just a quick google search away. Instead, I’d like to focus on the lack of research or available information on the said ‘mellowing’ of acidity as you allow something to age. From the little information out there, it seems like the total acidity on whatever you’re aging remains constant, even in bottles of wine. What does change however, is the perception of acidity upon consumption.

This is probably due to a mixture of factors, such as the different compounds produced by the aging process and their interaction with acid, the breakdown of some acids into different types, and the idea that our tongues perceive some types of acids as more mellow. While citrus juice does tend to taste slightly better after a few hours of enzymatic bittering when the balance of bitterness and acidity is just right, citrus juice does tend to become too bitter after that. As such, whatever it is, I doubt the ageing of ponzu sauce has anything to do with enzymatic bittering as a week is much longer than needed for the reaction to go to completion. Instead, I think the ageing of ponzu sauce has more to do with giving time for the various flavours to meld together, a little bit of oxidation and a little bit of the maillard reaction. I’d say this is similar to aging lemons moroccan style or ageing yubeshi.

Thirdly, a good ponzu sauce is made from high quality citrus juice and typically a blend of them. I have heard somewhere that the original ponzu sauce is made from the dai dai citrus fruit (橙/だいだい/C. ×daidai) which is the asian variety of bitter oranges. However, most ponzu sauces on the market are made from a wide mixture of Japanese citrus such as sudachi, yuzu and kabosu, which you’d be familiar with if you’ve been following this site. Occasionally, you’d find the rare ponzu sauce made from yuko, which is an even rarer citrus fruit in Japan.

Zuboraya’s Ponzu Sauce Recipe (づぼらや のポン酢の作り方)

As most of these recipe recreation efforts go, your best shot is to start with whatever hints you can find, which in this case is the back of the bottle of Asahi’s Ponzu sauce. So ignoring the additives that you’d usually find in a bottle product in order to make it shelf stable such as caramel colouring, acidity regulations and protein hydrolysates, you find an interesting combination of ingredients in their ponzu sauce which are:

- Soy Sauce

- Sudachi, Yuko and Yuzu Juice

- Vinegar

- Salt and Sugar

- Rishiri Kombu

- Mirin

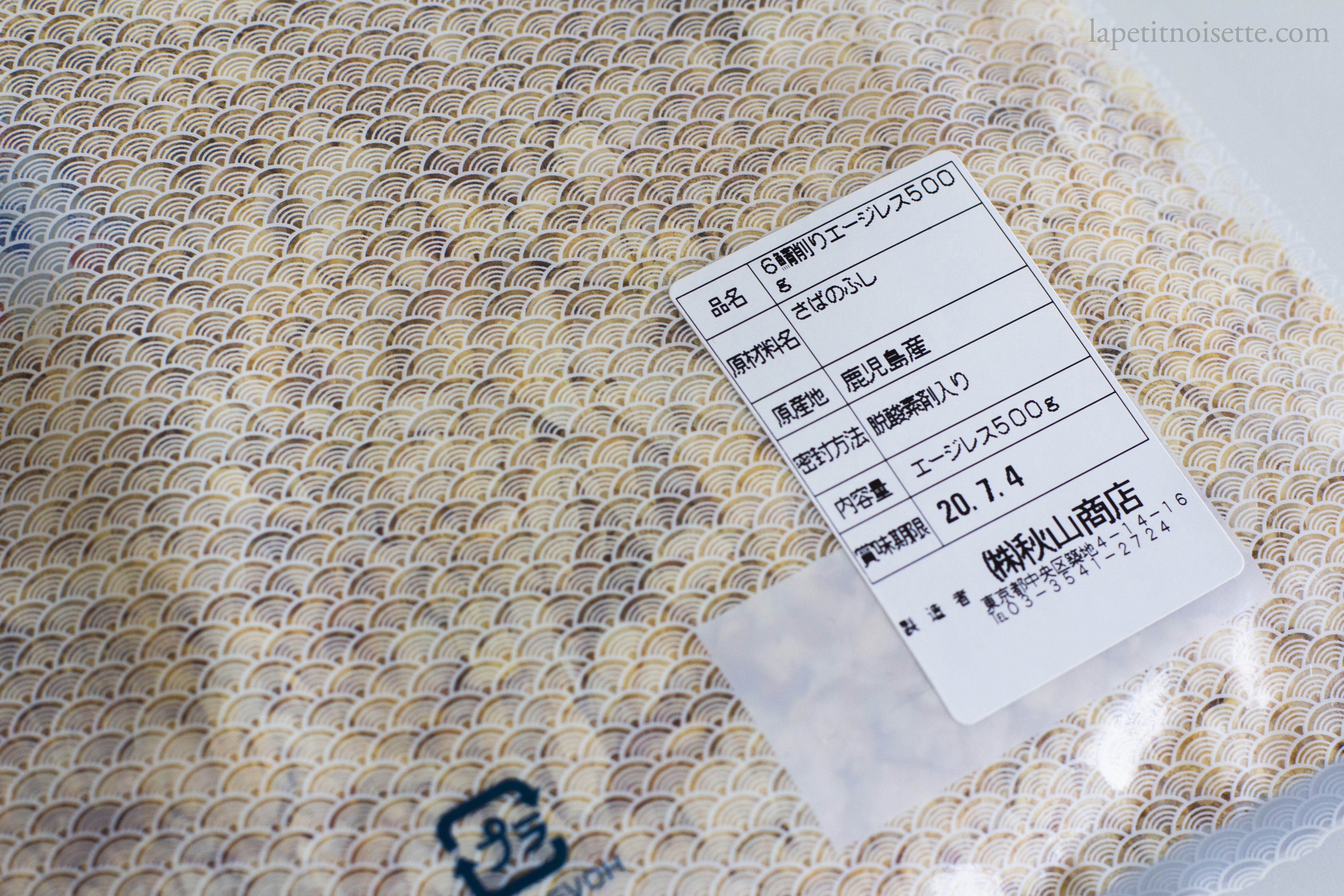

- Dried Sardines, Mackerel, Bonito and Soda bonito

- Dried Shiitake

Let’s break down this recipe. Instantly several very different things jump out straight at you. First, the use of 4 kinds of dried fish in their ponzu sauce. From what I know, conventionally only dried bonito (katsuobushi) is added into ponzu sauce as it has the highest concentration of savory notes whilst other kinds of dried fish are suppose to impart a more fishy taste, especially for dried mackerel, which is used in udon soup more than anything else. Dried sardines as well are normally used in soup stocks for ramen rather than sauce. Soda bonito is probably the rarest ingredient of them all, which is the dried version of a small bonito called soda katsuo (そうだかつお). The dried version of this fish is called sodabushi (宗田節) and can only be found in specialist shops.

The next thing which is not unheard of but considered unconventional is the use of dried shiitake mushrooms in their sauce. Your typical sauce of glutamic acid in most Japanese high-end cuisine is solely kombu and katsuobushi as they’re the most refined and concentrated. You’d typically find the use of dried sardines and dried mushrooms in a korean-style soup stock instead, so I was surprised to find this here. Lastly of course, there is the addition of yuko which is a hard to find citrus fruit.

So, after many tests to find the right balance, the main takeaway I have from this recipe is it’s feasibility only when produced in volume. To explain, let’s look at the most common ratios for ingredients that I have found and have tested (in bakers percentages with soy sauce as 100%):

100% : Soy Sauce

110-120% : Vinegar + Citrus Juice

15-20% : Mirin + Sake

5% : Dried fish

3-5% : Dried Seaweed

These ratios in my opinion are actually a masterpiece, after all, having more acidity from the vinegar and citrus juice compared to the salty soy sauce gives it its characteristic tangy mouthwatering profile, with the mirin and sake providing the undernotes of sweetness that are finally rounded out by a small amount of savory notes from the dried ingredients.

However, given that you only have 5% of weight in dried fish, to be able to incorporate 4 kinds of dried fish in your recipe means that you have to be at least using 1 litres of soy sauce (which equates to 50 of dried fish) which would make 2 litres of this ponzu sauce! Extremely unsustainable for a non-restaurant or business in my opinion. So unless you happen to have bags of these kinds of dried fish already open (maybe you’re a big ramen nerd or live in Japan) it’ll be hard to follow along here, but for the sake of completion, here goes:

150ml of Aged Tamari Soy Sauce

850ml Kokuchi (dark) Soy Sauce

500ml Rice Vinegar

350ml Yuzu Juice (~2kg of fruit)

350ml Sudachi Juice (~2kg of fruit)

200ml Dai Dai Juice (~6 oranges)

150ml of Mirin

10g of Rishiri Kombu

20g of Shaved katsuobushi

20g of Shaved sababushi

2 small pieces of Soda Bushi

5 large Dried Sardines

- Add the mirin to a sauce pan and bring to a boil to remove all the alcohol, until ~7-10% of the volume has evaporated. Allow to cool.

- Squeeze all the citrus juices into a bowl, ideally using only your hands as a mechanical squeezer may over squeeze the citrus. If not, at least hand squeeze the sudachi and use a squeezer for the Dai Dai and Yuzu. Strain out any pith or seeds.

- Add all the ingredients into a jar, ensuring the kombu is fully submerged.

- Allow to macerate and steep for 7 days in the fridge before straining out the kombu and dried fish.

- Store in an airtight non-reactive jar for 3 months in a cool dark place before using.

Notes:

So the original recipe does not use Dai Dai juice but Yuko juice but I feel as though the bitterness from Dai Dai juice is important for this recipe plus Yuko is extremely to find inside Japan yet alone outside. You can substitute Dai Dai juice with seville orange juice. The recipe also contains dried mushrooms but no matter what quantities or quality of dried mushrooms I tried, I just couldn’t get the taste right and I found it hard to believe the original Zuboraya used dried mushrooms in their ponzu, it’s just too… mushroomy? I also did add some sugar and salt, the recipe itself contains enough salt from the soy sauce and sugar from the mirin, and I didn’t see the point of adding cooking sake. The problem with cooking sake is that it can be quite harsh unless you use good quality cooking sake, which is basically drinking sake, which is not worth adding in this recipe as you have the taste of rice from the rice vinegar.

How to make your own ponzu sauce recipe

100% : Soy Sauce

110-120% : Vinegar + Citrus Juice

15-20% : Mirin + Sake

5% : Dried fish

3-5% : Dried Seaweed

Going back to the ratios above, it’s through the slight modification of these ratios that you can design your own ponzu sauce and how much you want to spend on it. If you want more sweetness in your ponzu sauce, just use mirin without any sake at all. If you want more citrus notes then feel free to use 100% citrus juice without any vinegar but if you want more bitterness add some bitter orange juice into your citrus juice mix. Highly aged tamari can also contribute some bitterness to your ponzu so you might consider using 10% tamari and 90% light soy sauce instead. If you want, you can even go all out and use expensive soy sauce to make this sauce if your consumption volume is high enough. Same goes for the dried ingredients. If you just can’t find them, you could always substitute with a pinch or two of MSG powder. The possibilities for how you can design your own ponzu are endless.

Michelin Starred Ponzu Sauce Recipe (赤酢ポン酢)

At the restaurant, we made a much simpler version of ponzu sauce that we used the day itself. In hindsight, it actually makes sense why the long 3 months aging period for the ponzu sauce we used was not necessary, as we substituted out the rice vinegar with red akasu (sake lees vinegar) and used 3 years aged mirin so it was already mellow enough. Kombu and katsuobushi was not used as the red sushi vinegar had already enough savoriness to it. The citrus juice we used was green yuzu and green sudachi. Green unripe yuzu is not uncommon to use in restaurants but much harder to find outside. The recipe is as below:

100ml of Soy Sauce

35ml of Sudachi Juice

35ml of Green Yuzu Juice

40ml of Akazu Vinegar

20ml of 3 Years Aged Mirin

Squeeze the sudachi and green yuzu into a bowl and strain out any seed or pith. Combine all the ingredients together and use.