Maguro (鮪) Tuna Information and How to Dry Age Tuna.

Read an earlier article going in-depth on the science of ageing fish.

Maguro, or bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) is the species of tuna that is consumed in Japan, most famously as sashimi. Formerly sold at low prices, the price of Maguro started to skyrocket after World War 2, with it sometimes being attributed to the increase demand in the Japanese market of red meat due to the their belief that eating more red meat would allow them to grow as large as their American counterparts (which they felt inferior in size too during the war). This fact is hard to verify but one thing for sure is that the price of Maguro started to increase exponentially until today, especially for the fattier cuts from the belly of the tuna which are highly sought after and thus unaffordable and considered a delicacy.

The price hike of bluefin tuna is also attributed to the decrease supply of tuna due to its declining population, so much that it is now considered an endangered fish due to overfishing. Because of this I do not advocate the consumption of bluefin tuna, but other sources of sustainable tuna such as yellowtail tuna.*

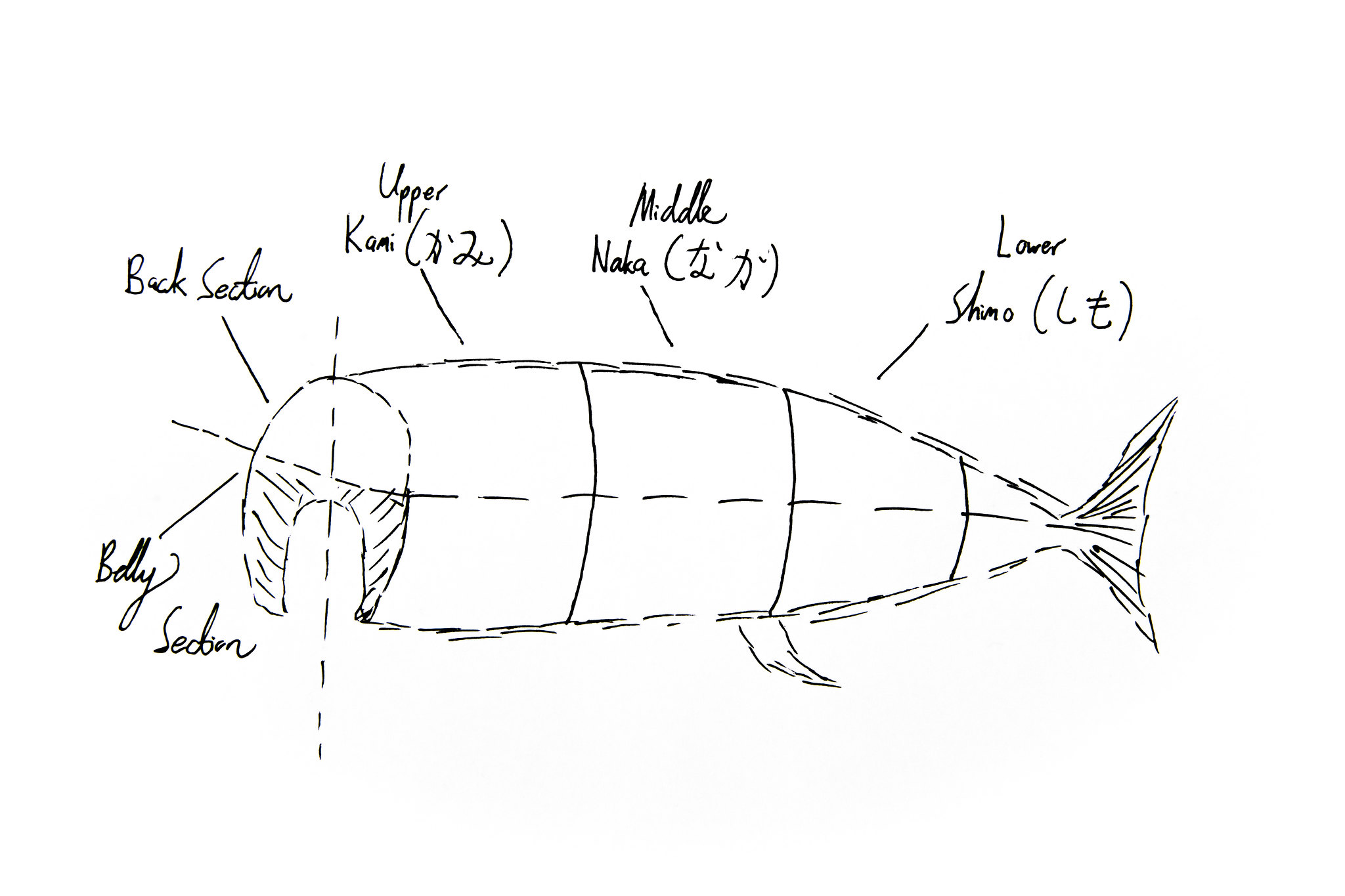

When cut, the body of the tuna can be separated into multiple 3 separate parts (not including the head). The front third of the tuna just behind the head (known as the kamashita かました) is called the Kami (かみ), the middle section is called the Naka (なか) and the tail section is called the Shimo (しも). Each of this sections in turn can be split into the upper back section and the lower belly sections and shown in the diagram below that I drew. (Sorry if the diagram isn’t clear!)

There are 4 kinds of sashimi cuts that can obtain from the body of tuna (in ascending order of fattiness, price, and rarity):

The pure red flesh without any fat known as Akami (あかみ)

The semi fatty flesh that has a gradient of fat known as Chutoro (ちゅとろ)

The fatty marbled belly flesh known as Shimofuri Otoro (しもふりおとろ)

And the sinew and fat rich under belly known as Jabara Otoro (じゃばらおとろ)

The belly section of the Kami and Naka contain all 4 kinds of flesh, while the back section of the Kami and Naka only contain Akami and Chutoro. The belly and back section of the Shimo only consists of Akami and is thus the cheapest in terms of price.

Jabara Otoro which comes from the underbelly of the fish, is the richest in fat but also contains the largest amount of sinew. This sinew causes the flesh to be extremely chewy but if allowed to age and mature properly, will literally melt in your mouth. The ageing of this cut must be done properly, over-aged and the colour of the flesh will become dull and brown due to oxidation with a pungent taste and mushy texture. Under-age the flesh and it will be too chewy with a lack of taste. (more on this later!) Shimofuri Otoro has less fat compared to Jabara Otoro and has almost no sinew. This makes it a much popular cut to be used by restaurants as it is easy to be crafted into nigiri and is easier to process as it requires less ageing and is harder to go wrong. Jabara and Shimofuri Otoro from the Kami section of the tuna has significantly more fat and sinew compared to the Naka section and therefore is more sought after by high end sushi restaurants and chefs who are able to appropriately mature the flesh. Chutoro is a moderately fatty cut of tuna that many people enjoy due to its gradient of fat. This means that it still has the intense acidic flavour of Akami but with the fat of Otoro.

On Rigor Mortis and Aging Tuna

After a tuna dies and undergoes rigor mortis, the taste of the tuna continues to develop through enzymatic reactions and the breakdown of various molecules. The slow controlled breakdown of these molecules are important to the taste of the Tuna. Read more on rigor mortis.

During the ageing and maturing of tuna, not only does the concentration of inosinic acid increase, but the various enzymes in the tuna (proteases) start to breakdown proteins into smaller amino acids which also increases the flavour of the tuna. Furthermore, the oxidation of fat in the tuna further helps in adding complexity to the taste due to the slight increase in funky acidic taste that it contributes. As with most aged or fermented products, the point at which something can be considered to have gone bad is neither black or white but more on a spectrum. Therefore some people would prefer tuna aged for a longer period of time whilst some people would prefer tuna that is not aged at all.

In very rare circumstances where you are able to obtain a piece of tuna before it has fully undergone rigor mortis, cutting into this tuna will cause the flesh to crimp or dent after a while as the muscle continue to contract. This causes the flesh of the tuna to be extremely hard to cut and tough to eat. This is known in japanese as chijire (縮れ). This damage can be undone using appropriate ageing methods as described below.

This belly section of tuna from the Naka section is so fresh that the muscle contraction can be seen by how to end of the slab on the right side of the picture is still being pulled away from the chopping board. Cutting into this would cause it to crimp and thus it needs to be aged.

Ageing vs Rotting

If fish is just left in the fridge without proper care, it basically starts to rot instead of age. What causes this difference?- water content. If the water content on the fish is too high, bacteria growth is promoted which then causes the fish to start to rot. The reverse is also true. A fridge is an extremely desiccating environment and if the skin dries out and desiccates too much, the flesh of the fish will be damaged and the texture will be ruined. This is why fish is usually aged by being wrapped in two paper towel before being wrapped in a plastic bag. This package is then placed in ice or in the fridge. The paper towels absorb moisture from the fish but still keep the fish in a semi moist environment, whilst the plastic bag protects the fish from the outside environment. If the fish is aged in a plastic bag alone without the paper towels, There would be too much moisture in the bag and the fish will start to rot. (Magu or Rido paper リードペーパー is a special water and absorbent paper developed by the Japanese to absorb water whilst still maintaining the quality of the fish, it is sort of a thicker version of butcher paper).

Temperature wise, the ideal temperature for ageing fish is between 1-6 ˚C as any lower might cause ice crystals to form, thus damaging the flesh of the fish, whilst any higher would cause the fish to rot.

In Japan, tuna itself is usually aged for 7 to 10 days by the fishmonger before being sold to the restaurant. The restaurant themselves then continue to age the tuna for 3 to 4 days and up to a week if the tuna is extra fatty. This period is substantially shorter compared to that of beef (which can sometimes be aged up to 60 days), but has around the same effect due the significantly less fat tuna has compared to beef (other fishes are aged for only 3 to 4 days).

Recipe to Age Tuna

Given the high cost of tuna, the risks of aging tuna and not getting it right is high and the consequences dire and thus you may want to proceed with care. The following is a 3kg slab of belly from the Kami section of the tuna brought at the Nagahama Fish Market (長浜鮮魚市場) in Fukuoka.

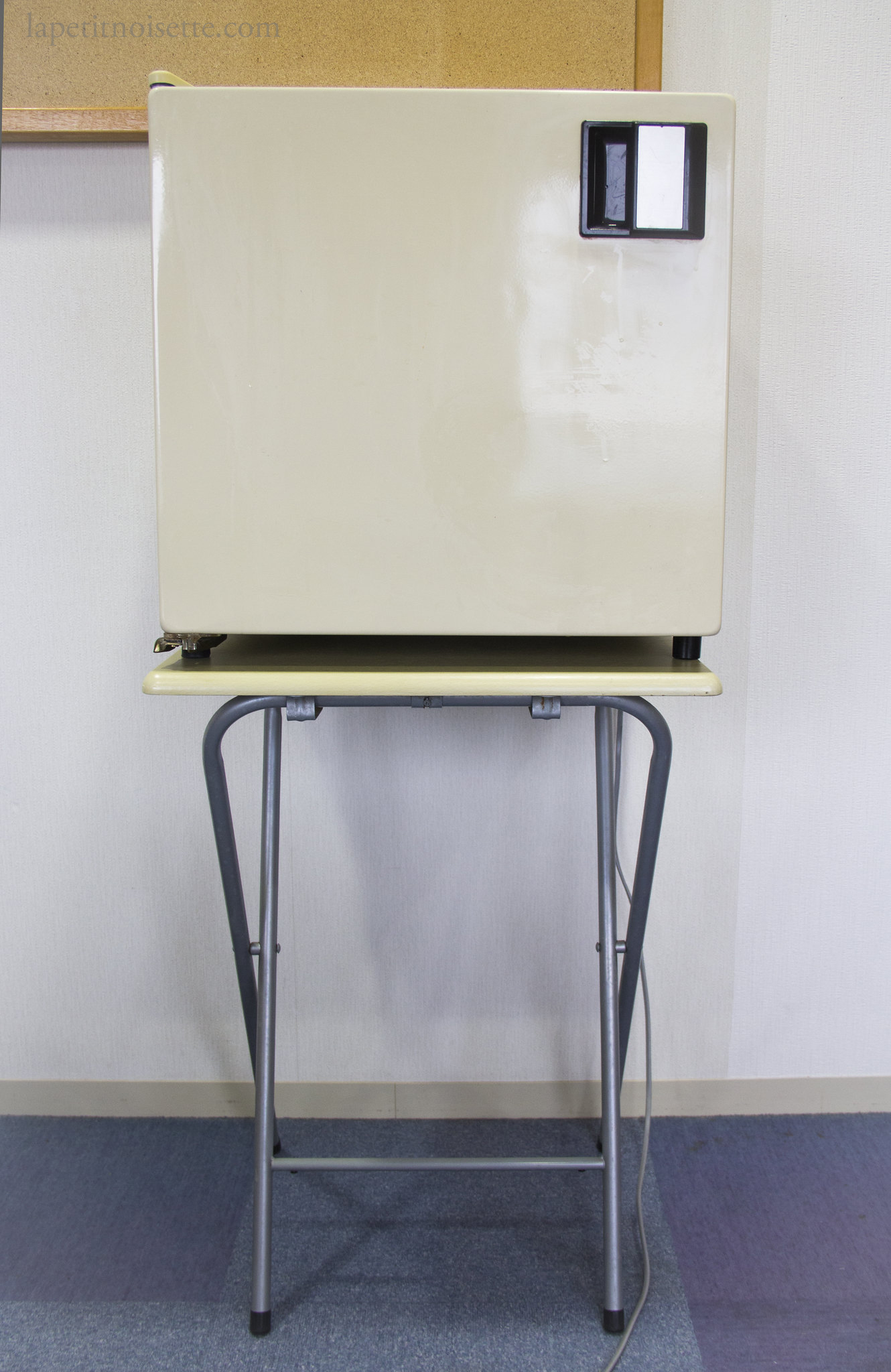

The entire process below can be replicated using a water-cooler filled with ice and water, with the ice refilled everyday to maintain the temperature. In my process however, I took a small fridge and sanitized the entire inside with bleach diluted with water before starting the ageing process.

The tuna belly I purchased deliberately did not have the skin, fat cap or muscle where the blood line runs removed. This because these all these parts help to protect the fish as it ages. The dark red muscle you see at side of the meat is where the blood of the fish run through. This gives it its dark red colour as well as an extremely bitter taste, which is why it is normally removed and discarded.

The fishmonger at the market had already been ageing this tuna in a special fridge for 5 days before I purchased it and continue the ageing process myself. Using a clean sheet of paper towel, I first wiped off all the moisture and blood from around the tuna before wrapping it in a layer of Japanese fish paper (you can use paper towels), followed by butchers paper in green. I wrapped the fatty part of the tuna separately from the lean meat (Akami) with a different paper towel but it doesn’t matter.

After wrapping, the fish is placed in a large plastic bag and all the air is sucked out of it with your mouth (a standard practice in most restaurants) before being tied up. This minimises air expose and prevents the fish from oxidising quickly. A much better technique in my opinion would be to use a vacuum back machine set at 80 to 90% vacuum. This was then placed in the fridge at 1˚C for two days.

During the entire ageing and maturing process, the quality of the fish should be checked on everyday, with the brightness and redness of the fish being monitored. The fish should not be going slimy, should not be wet to the touch, and still should maintain its bright red colour. Through the ageing process, you should be able to feel the fish becoming more tender to the touch, as well as the fat becoming more aromatic. The best way to monitor the ageing of your tuna is actually by smelling it everyday when you wipe it down and see how to smell changes over time. It also helps to gently press the fish to see how its texture changes.

After two days, the Akami would have been aged appropriately and ready to be eaten. Because of this, I then removed the slab of tuna from the fridge, unwrapped it and then proceed to remove the Akami. This is first done by removing the bitter dark red muscle from the tuna, using a sharp knife to cut between the dark red muscle and Akami it as shown in the photo. Slowly peel back the muscle as you cut it out.

Next, cut the Akami away from the fatty part of the tuna by holding the knife horizontally and cutting through the slab horizontally, where the Chutoro meats the Akami.

The remaining slab of tuna now contains the Chutoro, Jabara and Shimofuri Otoro that needs to continuing being aged. As with before, this slab is then wiped down, wrapped in fish paper and butcher paper, before being wrapped in a plastic bag. This package is then returned to the fridge to be aged for the next 3-5 days (whilst also checking it everyday).

My slab of tuna, which was approximately 2.5kg at that point (with the Akami removed), was fully aged and matured by 4 days. If aged for longer than that period of time, I felt as though the red colour would be too dull presentation wise, whilst the fat would have begun to over oxidise. This would also mean that the sinew in the Jabara Otoro would be too weak to hold the flesh together to make nigiri with.

This was the time to slice the tuna into blocks or saku (さく), ready to be converted into nigiri. To begin, separate the Chutoro from the Otoro by slicing down the slab where the fat cap almost completely covered the meat. The ratio of Akami, Chutoro and Otoro in a piece of Kami tuna should be around 2:3:4.

From here, continue to slice straight down the slab vertically to obtain rectangular sakus at around 2.5-3 cm in thickness. Do not remove the fat cap and skin from the sakus until it’s time to serve it, at which time the fat should be removed due to it’s tough texture and strong smell. For the Akami, slice off the membrane of the fat cap and dark red muscle that remains on the block of Akami. Cut the Akami into vertical slabs the same way it was done with the Chutoro and Otoro.

The various sakus of tuna are now ready to be used as nigiri toppings or just as sashimi.

The sakus of tuna should now be stored in a container in the fridge whilst being wrapped in fish paper or paper towels to protect them. If the Akami starts to look dull due to blood oxidising, it can be marinated in nikiri (a mixture of soy sauce, mirin, sake and sugar) for 30 minutes (for an entire uncut saku).

In terms of special cuts of tuna nigiri that can be obtained from the tuna, the block of Jabara Otoro is sometimes not cut into sakus but kept as an entire block. The fat cap on this block is then horizontally cut off and slivers of Jabara otoro are then shaved off horizontally from this block, folded together and assembled into nigiri as shown in the photo.

The width of the sakus are sometimes too wide to be used in nigiri and are thus trimmed down. An Chutoro saku should be trimmed at the fattier size in order to preserve the lean to fatty gradient of the Chutoro.

This trimmed but is around the length of a pencil and is known as the “King of Chutoro” in Japanese, or also as the pencil of Chutoro (Enpitsu 鉛筆). This can be folded onto itself as nigiri or served as a roll.

*What struck us as appalling living in Japan was actually the attitude you typically encounter when when talking about eating endangered species such as whale and bluefin tuna. Instead of the usual- “it’s going extinct and therefore we should stop eating it and let the population recover.”, we mainly heard “it’s going extinct and won’t be around for much longer and therefore we should eat more of it!”

Phil, can you share your experience with edomae sushi?

We tried traditonal edomae sushi for the 1st time at a sushi restaurant in Tokyo that has been around since 1861 in the Kudanshita area. We went for lunch b/c lunch sets are more affordable for 4 (2 adults, 2 children). The taste and look of the nigiri are different when compared to modern sushi.

Taste — much saltier if one is accustom to how sushi tastes now. The vinegar has a muted taste, unlike common rice vinegar — this is good. Maybe the nigiri was salty b/c historically sushi stalls did not have electricity, nor refridgerators. *Is this expected?*

The rice was brown. I suspect this is caused by the use of red vinegar you wrote about.

The maguro nigiri was cut with sinew intact. We had a tougher time chewing the nigiri. Of course this was intentional. When my wife and I prepare sushi at home, we cut around or peel off the sinew. I was wondering…

– Did the chef give us a traditional experience where nothing is wasted.

– Or lunch sets are prepared with cheaper cuts

– Or the chef was giving us a message that we weren’t welcome.

*Is leaving the sinew in place expected?*

(The proprietress was very nice, when she came in from the rain, she thanked us from dining with them).

Hello,

I think the answer to your question is more complicated, so I’ll try and answer it below:

Whether or not the sinew on the tuna is removed from depends on the cut of tuna. Even the part of the tuna that we would classify as otoro is large enough to have different parts with sinew of varying toughness. When aged, some of the sinew does soften up but if it was chewy to the point of inedibility, it sounds like it was most probably some bad luck. It isn’t necessarily the experience where nothing is wasted. At the restaurant I worked at, we used a spoon and knife to scrape the soft meat off the sinewy parts of tuna to make a tuna mince for rolls, so its not common for people to be served tuna with tough sinew. The fish used for lunch and dinner can differ for price, but that difference tends to be the species of fish served but not the parts of the fish. The exception for this is of course tuna, where some lower end places might do akami and chutoro for a cheaper set, and only include otoro for the more expensive sets. However if you were promised otoro or if it were part of the set, its extremely unlikely (read impossible) that the chef used a cheaper cut. From my experience restaurants will use the same quality of cut for all customers, regardless of cheaper or more expensive sets.

This points to 2 more likely scenarios, the first less likely being that of the tuna that the restaurant was supplied with, you were unlucky enough to dine there when the tail end (as in last bit) of that week’s stock was being served and as you’d know as you’ve cut tuna yourself, some parts just have more sinew. If that was what they had left, that would have been what you got. The second more likely scenario though is that the restaurant overall is supplied with lower quality tuna. As mentioned above “restaurants will use the same quality of cut for all customers”, but if the tuna the restaurant is sourcing is low quality to begin with, then all customers will just get that same low quality.

The sad thing about the sushi restaurant industry currently is that the price of fish (especially tuna) just keeps increasing and even if the price doesn’t increase, the quality of fish keeps decreasing. This means its extremely hard to serve higher quality fish at an affordable price, especially when the top quality fish is exported to high end sushi restaurants in the US, Hong Kong and Singapore. I know this is going to sound pretentious but nowadays I feel like if you’re after a legitimate traditional sushi experience, the cost in Japan per person for a meal is above 27000 yen, that’s because any lower and the restaurant won’t be able to afford the fish and still break even. Even when I go to Japan, I eat at the vast variety of cuisine the country has to offer, from udon to tonkatsu and yakitori speciality restaurants because they serve in my opinion, the highest quality food at a lower price. The highest ranked udon or tonkatsu restaurant on tabelog (Japan’s food ranking website) is always going to be 10 times cheaper than the reputable sushi restaurants, just because of the nature of the ingredients used. Fish is expensive.

I don’t know the price of the restaurant you went to, but most of the traditional countertop sushi establishments that will have the highest quality fish tend to be counter seating only (no tables) and don’t exactly welcome children. I don’t think the chef was giving you a message that you weren’t welcome, it’s just more likely that the restaurant can’t afford higher quality fish unless you pay a lot for it. Most of us outside Japan in the English speaking world know a lot about high-end sushi restaurants. Even this blog is about high-end sushi. However, there is also your typical standard sushi restaurant a Japanese family may go eat at during the weekend and I suspect that’s the kind of restaurant you went to. They have set lunches around 2000 to 4000 yen, are a solid good quality, and play an important part in society for a nice family meal or company work meal etc. I absolutely love them. They are not however, the kind of sushi restaurant that chase the expensive high end sushi making that this website is about and so won’t serve the highest quality tuna. It’s kind a of like expecting wagyu beef at your neighbourhood restaurant. It’s a different business model.

On the note about saltiness, if you look at my website’s recipe for sushi vinegar, there’s an addition of at least 15g of salt for 75g of vinegar, so it’s very very salty.

Sorry if any of this came across as a bit blunt, it was all typed out in a bit of a hurry. The main point is just that Japan does also have your standard mid-priced restaurants, even if they have a long history. If you have any more questions let me know!

Phil, thank you for the thorough answer, you covered all the angles.

We went to Sushimasa in Kudanshita on Wednesday (Jul 2022)

http://sushimasa-t.com

Maybe it was the end of the supply… the restaurants in Toyosu market are closed Wednesday, maybe the wholesale business is too. Unlucky.

I see your point about cost/quality ratio. A good craft beer can be had for less than the cost of good wine. Though recently the craft beers are starting to be the same price as wine.

How long does akami last ?

this article is very useful, thank you for making a good article