A good primer before reading this article is the science of making miso.

TLDR: Glass and plastic are good if you want your miso’s fermentation to be stable and consistent and relatively low maintenance. Wood is good if you intend to be making miso year after year and want to develop the community of organisms living in the wood. It is significantly higher maintenance.

To consider this question, let’s look into this from 3 standpoints:

- Practicality, storage and cost,

- Safety,

- And miso as a living ferment.

Practicality

If you’ve read through the series on making miso on this website, you’d notice that due to the emphasis on making miso the traditional way, our fermentation vessel of choice is Japanese cedar barrels with bamboo hoops. Practicality wise, it is highly unlike that this is the best vessel for you to use. Firstly, they’re not only extremely hard to buy, but in the event that you have the opportunity to buy one, they’re extremely expensive and do not warrant purchasing unless you’re definitely sure you’re going to invest time and money to make miso over and over again for many years. If you were just starting out and thinking of dipping your toes into miso making, I’d recommend a large plastic safe bucket of large glass jar as an alternative.

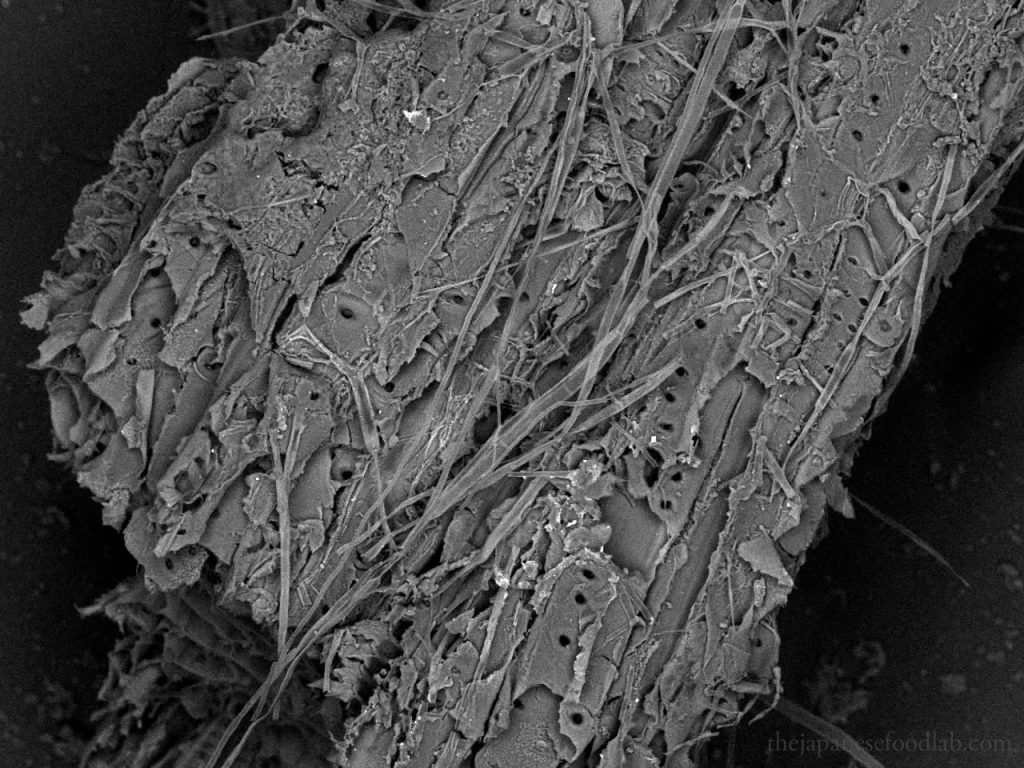

Real traditional cedar miso barrels are surprisingly fickle to take care of outside of Japan. If you happen to live in a hot and humid country, the barrels have a tendency to grow unwanted mould on them which can be particularly damaging if the mycelium (roots) of the mould grow into the wood, making it impossible to remove without damaging the barrel. Conversely, if you live in a country that’s dry with low humidity, the barrel staves have a tendency to contract as they lose moisture to the environment.

This forms gaps in the barrels which causes the liquid from the miso, known as tamari, to leak out. As this happens over months and months, it not only causes a mess, it also makes your resulting miso much drier than planned, which may cause uneven fermentation. In order to rehydrate the barrels, they need to be soaked in water for a couple of days before being filled with miso. When the finished miso is then harvested and removed from the barrels, the shrinking occurs again. This constant cycle of shrinking and expanding ultimately causes some of the staves to crack and bamboo hoops to splinter, causing permanent damage to your hoops.

Instead, non-reactive containers such as food safe plastic or glass are usually better alternatives when just starting out as they cost significantly less. They also work wonderfully as they will never leak (unless you crack them) and are also significantly easier to clean as they do not have creavises, indentations or grains where unwanted microorganisms can take hold and grow. It’s also possible to sterilise a glass container with hot water without the danger of damaging it. To me, the main downside of using glass is simply its weight and fragility. Especially when making large batches of miso, fermenting in glass quickly becomes out of the question due to the lack of transportability of large glass receptacles. Even at the restaurant I worked at, we mainly used glass jars when experimenting with new miso recipes as they were transparent, thus allowing us to see what was going on inside. However, when mass producing miso for the restaurant, we simply fermented them in large food grade buckets.

Safety

From a safety point of view, our main concern has also been chemicals from the container leaching in our miso. This is particularly important for miso in that we intend to age in the same vessel for long periods of time which increases the window of time through which harmful substances can leach out. This is true for all ferments, which is why we do not store kimchi (which is highly acidic), in plastic containers but in glass jars or traditional earthenware onggi. Luckily for us, miso is a relatively inert product which will not react with most containers. Miso is however, ever so slightly acidic, especially for misos made with less salt, as lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria tend to produce small amounts of acid. This is why some misos can have a hint of sourness to them. This small amount of acidity tends not to cause problems, but if you’re still worried, you can always ferment your miso in glass or ceramic jars to be 100% safe. With the advancement of plastic manufacturing technology, a lot of food safe plastic containers are designed to be able to withstand a certain level of acidity and alkalinity without breaking down or leaching chemicals. There even exists specially made acid resistant plastic containers to ferment kimchi. Therefore, I’d confidently say that all food grade plastic containers are safe to ferment miso in. If in doubt, it’s also possible to check the brand or product code of the container and check with the manufacturer (or google) if it’s acid resistant.

From a hygiene perspective, we’ve already established that glass, ceramic and plastic are much easier to clean than wooden containers, but the real question is: are they safer to use? The quick answer is that it’s complicated. It’s true that cleaning out and sterilising non-wooden vessels is a far simpler process, but let’s take a closer look at what is happening inside a wooden vessel. Whilst the gaps and crevices in wooden vessels can house harmful microorganisms, if used properly year after year, we can slowly cultivate a thriving community of helpful microorganisms such as yeasts, lactic acid and acetic acid bacterias. When fresh miso is added into these vessels, This community of microorganisms will quickly colonise the miso, making it extremely hard for harmful microorganisms to establish themselves and cause havoc. Before they’ve had the chance to multiply and infect our miso, our already prior-established community will be already present and able to outcompete harmful microorganisms. In fact, some traditionalists believe that if used correctly, fermenting miso in wood is far safer than glass, ceramic or plastic, where all traces of microorganisms, wanted or unwanted, are washed away each cleaning cycle.

The key takeaway here is simple. If you’ve never made miso before and are worried about hygiene, glass, ceramic or plastic is the way to go. However, if you’re confident in your fermentation ability and that you’re going to be making miso year after year after year in the same vessel, then a cedar barrel might be the way to go. After all, is it the same community of helpful microorganisms that keep your miso safe that also slowly gives each individual barrel its characteristic taste and terroir, allowing you to make miso that only you can produce.

It’s also worth noting that if you live in a dry location with low humidity, if gaps start to appear in your barrel from the wood contracting and miso or tamari start leaking out, this can provide harmful microorganisms an entry point into your otherwise sealed vessel. If you see mould growing on the miso leaking through gaps in the barrel, this can be a cause for concern.

Miso as a living fermenting

If you’ve learned anything from the sections above, it’s that miso is alive and is made up of a thriving community of microorganisms. Thus when thinking about the optimal container to make miso, we’ll want to think about how this container provides the optimal conditions for the microorganisms to thrive.

Whilst we already regulate the fermentation conditions through the salt content and fermentation temperature of the miso, another way fermentation is regulated is through the moisture content of the miso. (To find out more, read the section here on the science of making miso). In short, the higher the moisture content of your miso, the faster the fermentation and the dryer your miso, the slower the fermentation. However, too high a moisture content also brings the risk of certain bacteria in the miso getting out of control and contributing undesirable flavours, whilst too low a moisture content can cause uneven fermentation or fermentation to completely stop. The moisture content of your miso is largely determined by the amount of mixing liquid you add based on the recipe you’re following but the container you choose also determines how much evaporation occurs over time.

For glass or plastic jars which are non-porous, evaporation only occurs through the mouth of the container and thus you want a fermentation vessel with a wide mouth. If using a container with a small mouth, it prevents any excess moisture from evaporating and a huge build up of tamari soy sauce (the liquid pressed out of the miso by the fermentation weight). Whilst this is good if you wish to harvest the tamari for use, it can sometimes cause problems with the miso becoming slightly acidic as lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria thrive. A small mouth container also prevents oxygen flow and can be hard to remove miso from. Instead, we recommend using a wide mouth container to ensure a good flow of oxygen, easy cleaning and maintenance. If the humidity in your fermentation environment is too low, it’s much easier to put an inner lid and/or outer lid over your wide-mouth container to lower the rate of evaporation.

For wooden fermentation containers, you’d want to keep in mind that evaporation, though in small amounts, can still occur through the porous walls of the wood. This is especially so in a low humidity environment where the wood can shrink, allowing liquids to leak out.

Another important consideration is the permeability of your container to various gases. Whilst lactic and acetic acid bacteria do not require oxygen, yeast when deprived of oxygen start to produce alcohol, which can cause your miso to develop an alcoholic taste. To prevent this from happening, it’s important that some amount of oxygen can enter your miso. Conversely, acetic and lactic acid bacteria release carbon dioxide that needs to escape the miso, else off flavours akin to nail polish remover can start to develop. This is why miso cannot be made in airtight jars and is still made in vessels and containers, not in vacuum sealed packages. This is an added benefit of using wide-mouth containers as suggested above, as it allows for more oxygen flow into the miso. Wood here is especially advantageous over glass and plastic and the porous wood allows for gas flow in and out of the miso.

The last but most important idea behind miso as a living ferment is that wood is only fermentation vessel material where a community of beneficial organisms to your miso can establish themselves. Unlike wood, most materials do not have the pores, gaps and crevices in which a community of helpful microorganisms such as yeasts, lactic acid and acetic acid bacterias can thrive. This is especially when the wooden miso barrel is constantly in use and never left without miso for long. This allows each barrel of miso to slowly develop its own unique community, thus giving the miso made in different barrels its own characteristics and tastes. This is especially evident in the larger wooden miso barrels used by artisanal miso producers but will still be evident over the years in your own barrels at home.

Even in a single artisan’s workshop, there will be barrels that produce exceptional miso, and some barrels that produce sub-par miso. The key here is to cultivate a good community of organisms right from the start. This can be done using good fermentation practices learned through personal experiences in making miso. This is why we recommend wooden fermentation vessels for more experienced or ambitious fermenters. This is why almost no western restaurant will dare to use wood to ferment their miso for their menu. It’s not only expensive with high maintenance and risks, but may also lead to an inconsistent or subpar miso which risks not being able to produce enough product for service.

Even when growing koji on soybeans for soybeans miso, if traditional wooden koji trays are used, there’s always a fear that natto bacteria will take hold and ferment the soybeans before the koji is able to. If this happens, then the wooden trays may be permanently tainted with natto bacteria living in the wood. Whilst you can still produce delicious miso in non-wooden containers, we believe that truly exceptional miso is produced in wooden vessels. Whilst the maintenance and risks are greater, so are the rewards.