The majority of information here regarding the mining of iron sand in Kuji, Iwate Prefecture, were found from 2 sources. The first is an article titled ‘Iron and Steel Industry in Japan’, authored by Muzaffer Erslcuk and published by Clark University in volume 23 of a journal titled ‘Economic Geography’. The second is from the February 5th, 1927 issue of the Engineering and Mining Journal, in an article by James W. Neill titled ‘Iron From Beach Sands in Japan’, which was accessed from the Internet Archives.

Old cookware often carries with it a sense of craftsmanship and quality that is hard to find in modern equivalents. Not only are these older pieces often handcrafted or made in smaller batches, they’re often designed to last a lifetime and beyond. Unlike some of the mass-produced cookware of today, they are often heftier from being made with a greater amount of higher quality material. Ask any collector of vintage copper cookware and they’d tell you.

Sometimes however, the joy in owning an antique piece of cookware lies in the story it has to tell. In this article, we’ll take a look at the Kuji sand iron tempura pot, its significance in the evolution of tempura, and the history of iron production in Japan that it tells.

What is a sand iron pot?

When most people think of iron, they’re actually thinking of metallic iron – the pure elemental form of iron that is silvery-grey in colour, malleable, and a good conductor of electricity. However, the majority of the earth’s iron reserves are stored in iron ore deposits, which are geological formations that contain concentrations of iron minerals. These minerals include hematite, magnetite, goethite, and siderite, among others. Typically, the minerals are mined from the deposits and processed into iron ore pellets or sintered into iron oxides before being further processed into pig iron, which is the intermediate product obtained after smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron is then refined into various forms of iron and steel through additional processing steps such as casting, rolling, and forging.

In addition to traditional ore deposits, iron can also be extracted from sand iron, which is sand that contains high concentrations of iron compounds. While both traditional ore deposits and sand iron are sources of iron, they differ in their origin. Therefore, a sand iron pot, just like any other iron pot, is ultimately made from iron, but the source of the iron comes from sand iron instead of ore deposits.

In the modern world of high end deep frying restaurants in Japan, it’s rare to find anyone using a material that doesn’t have a high thermal conductivity. The famous tempura Kondo uses a traditional gunmetal pot, whilst tonkatsu Narikura uses a classic copper pot whose ability to heat up and cool down quickly is second only to silver. Meanwhile, tempura Niitome has opted to go with an aluminum pot, thus sacrificing some amount of even heating and thermal conductivity for lightness, but is still relatively quick to heat.

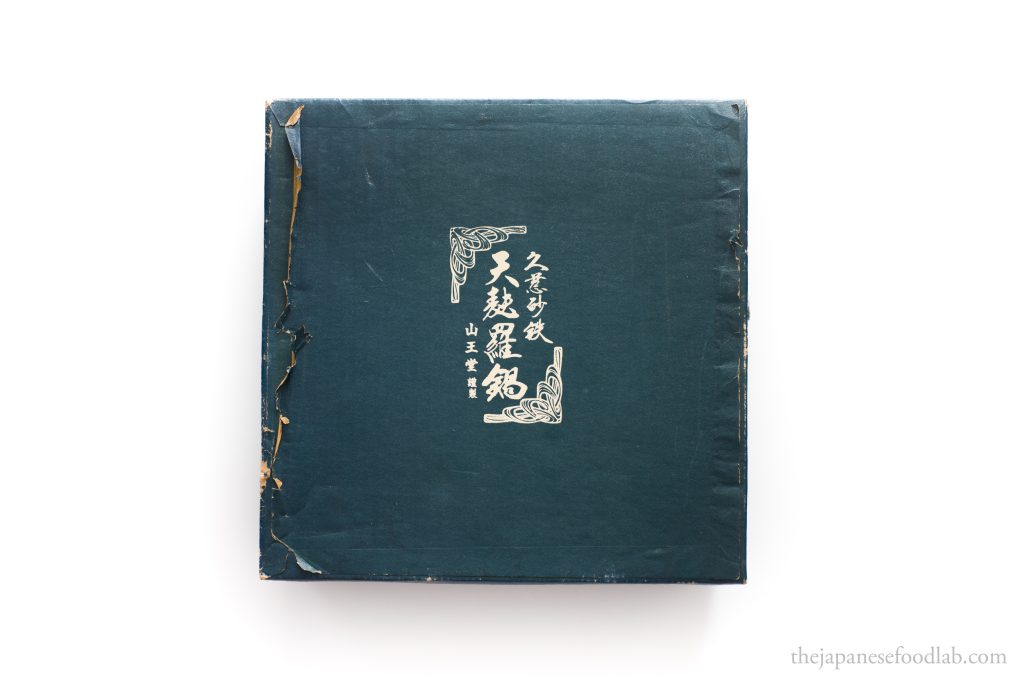

This hasn’t always been the case. Back in the 1900s, chefs were still experimenting with different materials and one that started to gain traction quickly was a tempura pot made from sand iron. One of the main producers of this pot that became highly regarded was company known as Sannodo (山王堂), located in Kuji City (久慈市) in Iwate Prefecture.

An overview of sand iron in Japan

But why was sand iron being mined in Iwate Prefecture?

Historically, a secure iron supply was important to a country’s national strength due to its importance in manufacturing military equipment. Unfortunately, Japan has faced significant hurdles managing their iron reserves compared to other iron-producing nations due to their lack of natural iron ore deposits.

To illustrate this, Japan only had 2 large iron ore mines between 1925 and 1945, the Kamaishi Mine in

Iwate and the Kutchan Mine in Hokkaido. Furthermore, what other iron ore deposits were available tended to be located in mountainous terrain, making it hard for transportation, or consisted of suboptimal mixed grades of ore. These factors combined made mining these deposits cost prohibitive and were only done so with financial subsidies from the government. In fact, it was actually cheaper during that period of time to import from overseas countries than to mine the domestic deposits.

In order to make up for this, Japan started to look at other potential sources of iron, one which was sand iron deposits. These deposits, originating from disintegrated granite, diorite, and volcanic rocks, contained a far lower concentration of iron ore comparatively and are deposited in layers of varying iron content, the best grade usually being at the top. They lie either upon the bedrock or upon other layers of sand and gravel of little or no value. The ore consists of magnetite grains, with limonite derived partially from the breaking down of the magnetite, together with sand, pebbles, and a small amount of large boulders.

The largest of these known sand iron deposits were actually located in the foothills near Kuji and have been known by the Japanese for centuries. It was said that the sword of the first feudal lord of Sendai, Date Masamune, was forged from sand iron from Kuji, and that it could cut through any other sword with ease.

However, sand iron mines, including the one in Kuji, faced similar problems- transportation between the mine and the beach was difficult and required significant investment, whilst the ore itself contained iron, a mixture of iron compounds that required a careful selection of metallurgical technique in order to increase yields to a satisfactory level.

As Japan’s high requirements for iron and steel were mainly for the purpose of national defense, after Japan surrendered in World War II, it no longer had the need to sustain a high level of iron production as its wartime requirements far exceeded current peacetime needs. This, combined with the high cost of running domestic iron production meant that many mines quickly ceased operations.

This also meant the end of the production of sand iron pots, along with the closing of the Sannodo business which specialised in creating sand iron cookware later down the line.

Why is the sand iron tempura pot famous?

Today, only one chef in the world of high end Japanese tempura is a proponent of sand iron pots- Tadashi Kusunoki (楠 忠師) of Tempura Kusunoki (天ぷらくすのき) who is renown for serving each piece of tempura by hand like pieces of sushi, to show that it holds no excess oil after frying.

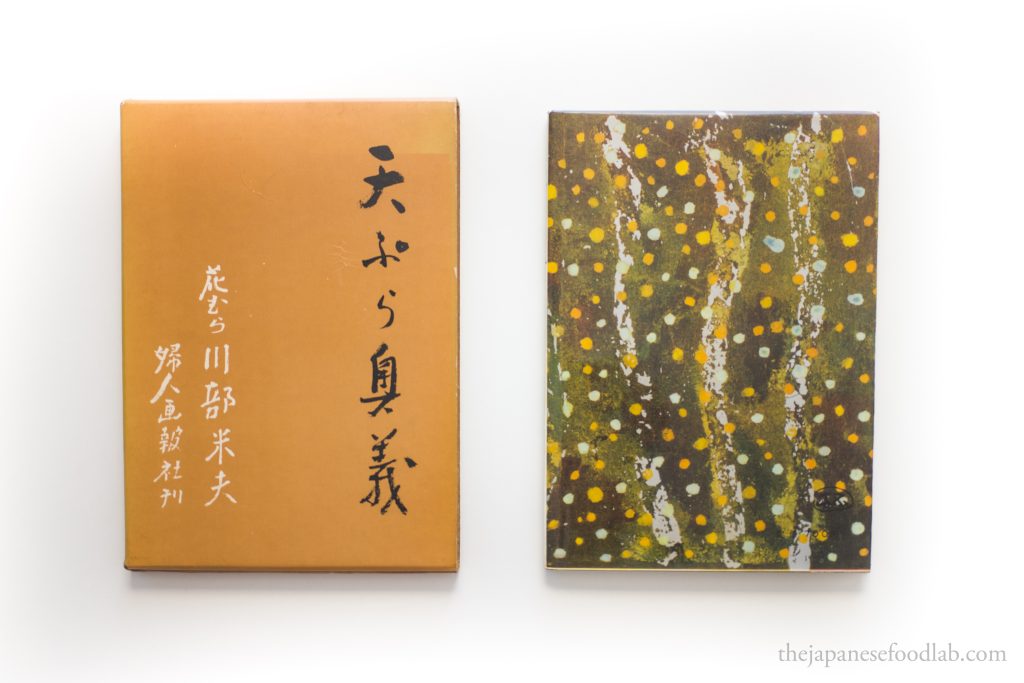

But before the rise of copper, this wasn’t always the case. Opened in 1923, one of the renowned restaurants of its time was Tempura Hanamaru (天ぷら花むら). This was before the days of food critics and review guides, meaning that a restaurant’s reputation was hard earned through word of mouth. Unique to its time, the then chef and owner Kokichi Kawabe (川部幸吉)* published a book titled ‘The Secrets of Tempura’ (天ぷらの奥義) in 1963 in which he outlined many of the guiding principles that form the foundation of our understanding of tempura today such as the importance of oil and the effect of heat control on texture. He also wrote about sand iron as the best material for tempura due to its high heat retention capabilities, which at that time period was the main source of information people could access if they wanted to learn about tempura other than actually working in a restaurant.

In fact, Tempura Hanamaru is still run today by the 3rd generation owner, Koji Kawabe (川部 幸二), and we hear that his children intend to take over the business. Sadly, times have since moved on and the restaurant is no longer highly regarded. This being said, it’s still worth a visit as a way to experience the style of tempura from the past.

We’ve also heard people say that famous imperial chef Tokuzo Akiyama (秋山徳蔵) from the Meiji era, was a big proponent of sand iron pots as ideal for tempura, and that he even wrote it in one of his many books, though we haven’t managed to verify it.

*The book was published under the pseudonym of Yoneo Kawabe (川部米夫).

Why is a sand iron pot perfect for tempura?

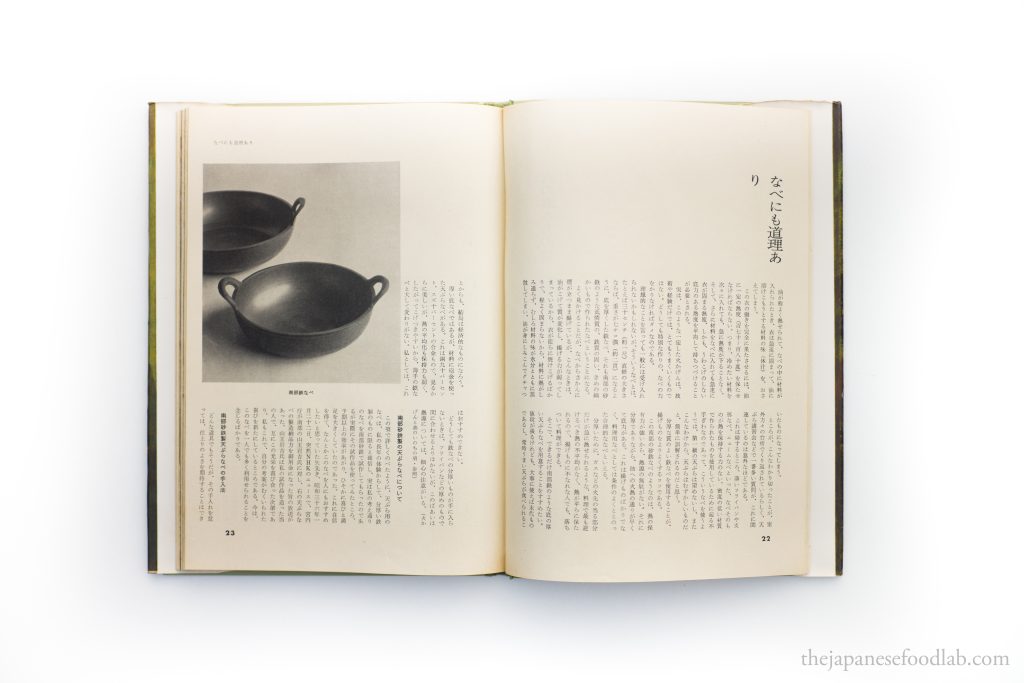

Everyone who uses cast iron pans knows that they take an incredibly long time to heat up, but once they heat up they stay hot for a long period of time. The same goes for a sand iron pot. Unfortunately, just because the source of iron is different, at the end of the day the pot is still made from iron which has famously low heat conductivity.

Many of the old resources mentioned above talk about how it conducts heat quickly but after doing our own testing, we believe that this idea has not stood the test of time and is no longer true, at least when compared against other common cooking materials today like copper, aluminium and silver.

What this pot has got going for itself is that the temperature of the tempura oil drops far less when fresh ingredients and batter are added to the oil, providing you with more stability and control when frying. However, this wouldn’t be any different from using a cast iron pot or dutch oven to do the same thing. If you look at recipes for deep fried chicken, it isn’t uncommon for them to claim that frying with a dutch oven is the way to go. Even in our original science of deep frying article, we recommended a Nambu cast iron pot before updating it later.

So what’s the point in buying one? The same reason why some people like collecting vintage items. They aren’t made with the same quality anymore. Most cast iron skillets and pots nowadays skimp on material and are not as durable. Even Oigen, arguably the most famous producer of cast iron cookware in Japan, only produces pots that are 2mm to 3mm in thickness. This is in contrast to Sannado sand iron tempura pot that is at least 7mm. You can see this happening everywhere in the cookware industry, from gunmetal tempura pots back in the day compared to copper ones today, to Mauviel, the most famous manufacturer of French copper pots, sneakily changing their definition of high quality from 2.5mm and above to 2mm.

This large thermal mass due to a thicker pot is especially helpful when using a smaller pot with less oil, as it helps keep the temperature stable. It doesn’t matter as much in restaurants because they use a much larger quantity of oil to fill their commercial sized pots, which means the temperature wouldn’t fluctuate much to begin with.

From our testing, this leads to crispier pieces of tempura which is what was prized back in the day, rather than a thin delicate layer of batter which is more common today.

Moreover, we personally love it because it provides us with an insight into the time period in which it was made, as well as the cultural and technological influences of the era. Understanding the story behind an antique cookware item can deepen one’s appreciation for its craftsmanship and significance. It represents a connection to the past and a tangible link to traditions, holding a special place in the hearts of collectors.

The design of a Kuji sand iron tempura pot by Sannado

Most cast iron pots you’ll find on the market are black in colour from the seasoning that has applied. This is primarily composed of polymerized fats and oils formed during the cooking process due to the Maillard reaction and the interactions between the food’s surface and the cooking surface. This provides a durable, non-stick layer on the surface of the cookware. More importantly, it prevents the cast iron surface from rusting when exposed to water.

The seasoning layer builds up on the surface of the cast iron over years of use, but nowadays, manufacturers typically apply a layer themselves before selling the product. Occasionally you can buy cast iron ware that hasn’t been seasoned and is grey in colour, and you’ll notice that it has quite a rough surface from the casting process, which also helps the seasoning to build up.

The sand iron pot is very different as it’s been completely polished on the inside without any seasoning, giving it a mirror like surface. Furthermore, if only used for deep frying, it will not develop a seasoning layer as food is never directly in contact with the material. This makes it easily prone to rusting, which is why it’s rare to find iron-ware that is non-seasoned, yet alone polish. If you look at many of the secondhand pots you see on sale, you’ll find that most of them have a certain amount of rust damage due to this.

You’ll find that some of them have a small indentation on the rim that’s supposed to act as a spout to pour used oil from. We find that this spout does not work well and can spill oil everywhere but we understand that this was probably the manufacturing constraints back in the day. Some of them also have three small ‘legs’ on the bottom to help them stand on a stove but many of them are smooth. On the bottom of the pot, you’ll find the words ‘Kuji Sand Iron Pot’ (久慈砂鉄) engraved into it.

From what information we could find, they were manufactured in 3 sizes, 24cm and 30cm for household use, and 40cm for commercial use. Due to the curvature of the sides of the pot along with ware and tear, you can find that they vary from 7mm to 8mm with the base being around 10mm thick.

Where to buy a sand iron tempura pot?

As of now, it’s only possible to purchase a sand iron pot from the second hand market depending on your luck if someone is willing to sell it, and the condition varies from used to slightly rusted. New unused ones are a great rarity and you are extremely lucky if you find one.