To find out more about other varieties of Japanese rice, see our main page.

In our previous article on how rice is evaluated, we introduced the Japanese Grain Inspection Association’s grading system as well as rice selection charts curated by people working in the industry. When we first delved into this topic, we thought long and hard about how best to represent a rice selection chart in a way that was easy to understand. We quickly realized that using a graph with simple adjectives would be the most accessible and self-explanatory and settled on a cartesian plane with mouthfeel firmness or stickiness (粘り) running from left to right and texture or sweetness (甘い) running vertically. Each individual variety is then plotted on this graph to allow you to judge one variety against another.

However, we felt that a lot of the subtleties and intricacies behind the different words were lost during translation. In an effort to preserve the nuances and full depth of the descriptions, we finally decided that whilst we would write this accompanying article to dive in depth into the words you’d typically see used to describe rice in Japanese, how they’re translated, as well as how these words may be better understood.

As you dig a little deeper, you’ll find that there exists variations in the words used to describe these axes and that they usually carry a slightly deeper meaning. As we struggled to define these words in the English language, we felt that the closest we could get to communicating the intended interpretation was by using anthropomorphic personalities to describe the rice.

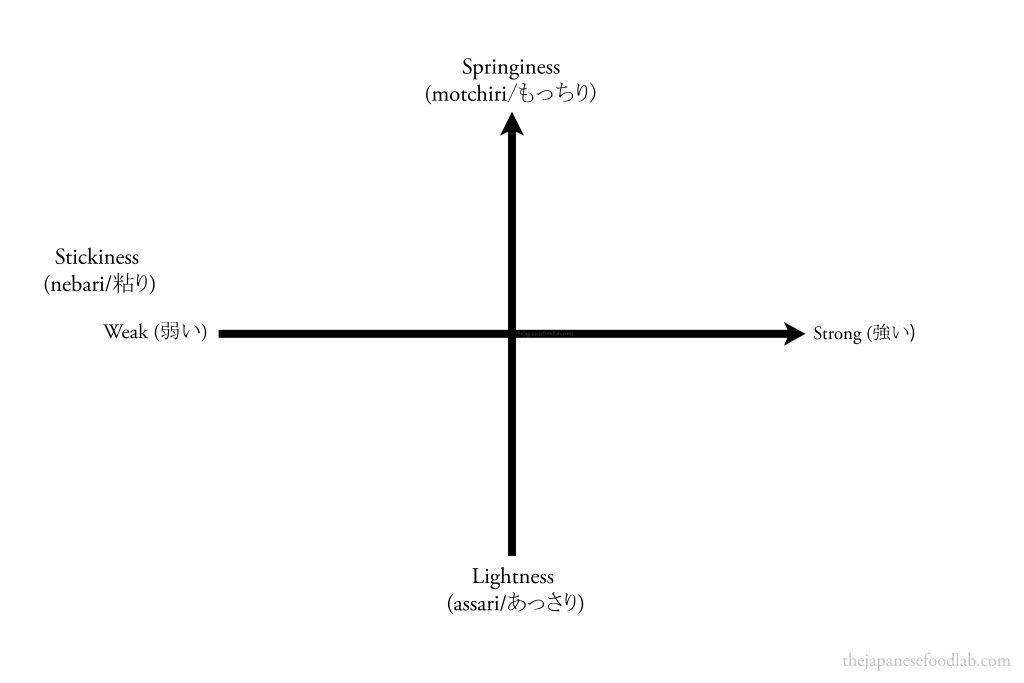

The x-axis: firmness or stickiness

The information trying to be conveyed in this axis is usually the initial perception of how the rice feels when it first enters the mouth. This tends to be described in three different ways, though you can interpret them as the same characteristic being evaluated:

- stickiness (nebari/粘り),

- ‘bite’ (hagotae/歯ごたえ),

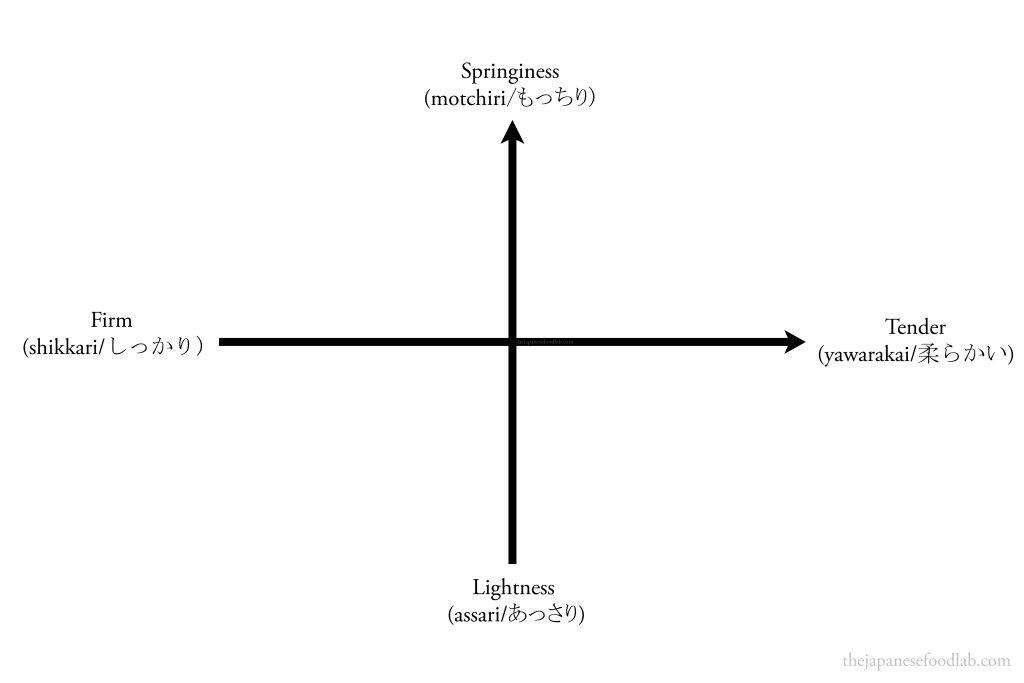

- or from firm (shikkari/しっかり) to tender (yawarakai/柔らかい)

After discussing the different adjectives, we decided to go with stickiness (nebari/粘り) as the x-axis for our website.

Nebari (粘り)

If stickiness is being assess (nebari/粘り), you’ll find it presented on a spectrum from ‘weak’ (yowai/弱い) to ‘strong’ (tsuyoi/強い). Something with ‘strong’ stickiness can also be denoted as being glutinous (mochi mochi/もちもち). You’ll also sometimes find it being assess as firmness where it will then be presented on a spectrum of hard (kata/硬) to soft (nen/軟).

Hagotae (歯ごたえ)

Occasionally, you’ll find it judged from the perspective of texture (shokkan/食感) or a more interesting word, ‘bite’ or chew (hagotae/歯ごたえ). In this context, it expresses the feel of the food when you first bite into it. Imagine having to fight an opponent whose skill is much greater than yourself to the point that it’s almost not worth fighting. This is a person who has a lot of ‘bite’ (is hagotae). Conversely, imagine having to fight a much weaker opponent where the idea of the person winning is almost laughable. In this case, the person does not have a lot of ‘bite’ to him (not hagotae).

Shikkari (しっかり) and yawarakai (柔らかい)

You might also find this characteristic evaluated from a spectrum of firm (shikkari/しっかり) to tender or plump (yawarakai/柔らかい). Rice that has ‘bite’ (hagotae) is firm (shikkari), and akin to a person who is certain and steady, with a solid personality that can be trusted. On the contrary, rice that does not have ‘bite’ (not hagotae) is tender (yawarakai), comparable to a person who is gentle and soft spoken with a personality that can be described as mild and flexible.

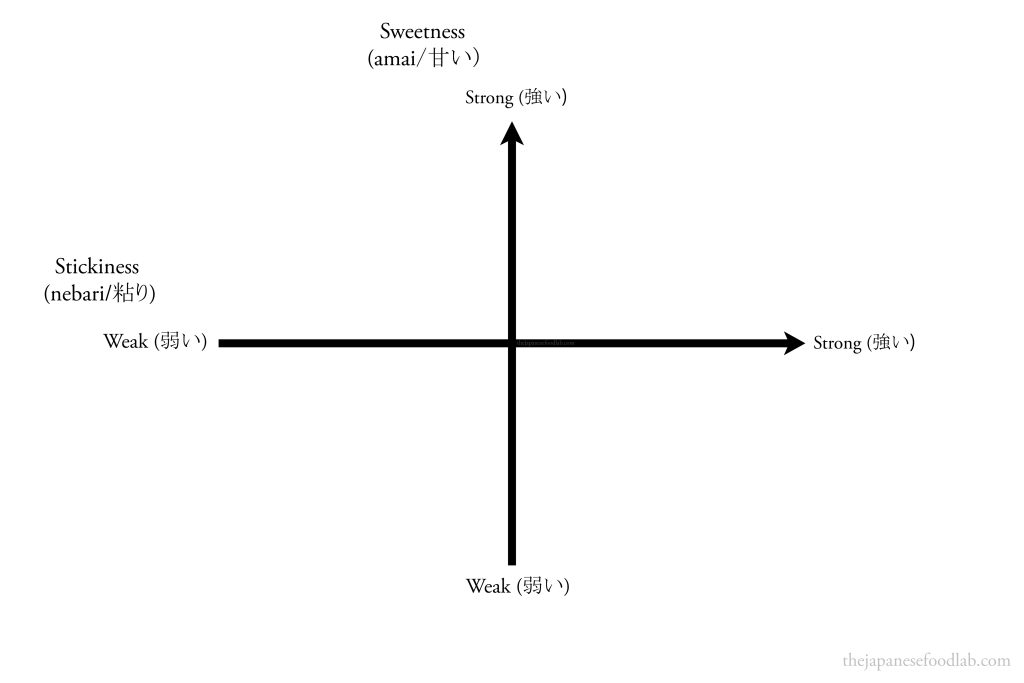

The y-axis: sweetness and weight

The information being described in this axis is usually the sweetness (amai/甘い) of the rice, but is sometimes described on a spectrum of lightness (assari/あっさり) to springiness (motchiri/もっちり).

After discussing the different adjectives, we decided to go with lightness (assari/あっさり) to springiness (motchiri/もっちり) as the y-axis for our website.

Amai (甘い)

When looking at sweetness, you’ll similarly find it presented on a spectrum from ‘weak’ (yowai/弱い) to ‘strong’ (tsuyoi/強い). It’s worth bearing in mind that rice that has a ‘strong’ sweetness isn’t the same sweetness as dessert. Instead, rice sweetness is much milder and is more noticeable on the back palate. It’s more similar to the hint of sweetness you may notice in sandwich bread.

Assari (あっさり)

The weight of the rice is sometimes used in tandem to describe the y-axis. As the weight of the rice is correlated with its sweetness, you can again interpret it as the same characteristic being evaluated.

Weight in this context does not refer to the mass of the rice, but instead the feeling of lightness or fullness it gives you after consuming it.

Rice that has a ‘weak’ sweetness (yowai), corresponds with lightness (assari/あっさり). To fully grasp its meaning, imagine a personality characterized by a bright and candid nature, exuding a hearty demeanor that is easy to appreciate. Similarly, the rice in question possesses a unique assertiveness in its texture, yet it maintains a smooth and effortless flow when consumed. Such a rice embodies an amiable disposition, making it a pleasure to enjoy.

Some people like to think of this characteristic from the perspective of what time of the day the rice is suitable to be eaten. Rice that is light (assari) is therefore suitable to be eaten for breakfast (asa gohan/朝ごはん) or in the summer as the temperature increases.

Motchiri (もっちり)

On the other end of the spectrum, rice that has a ‘strong’ sweetness (tsuyoi), corresponds with a texture that can be described as chewy or springy (motchiri/もっちり). This is said to be analogous to the elastic and cushiony quality of mochi rice cakes but is not to be confused with a glutinous or sticky texture which is already taken into account in the x-axis as nebari (粘り).

Rice that is springy (motchiri) is said to be more suitable to be eaten for dinner (ban gohan/晩ごはん) or during the cooler months of the year.

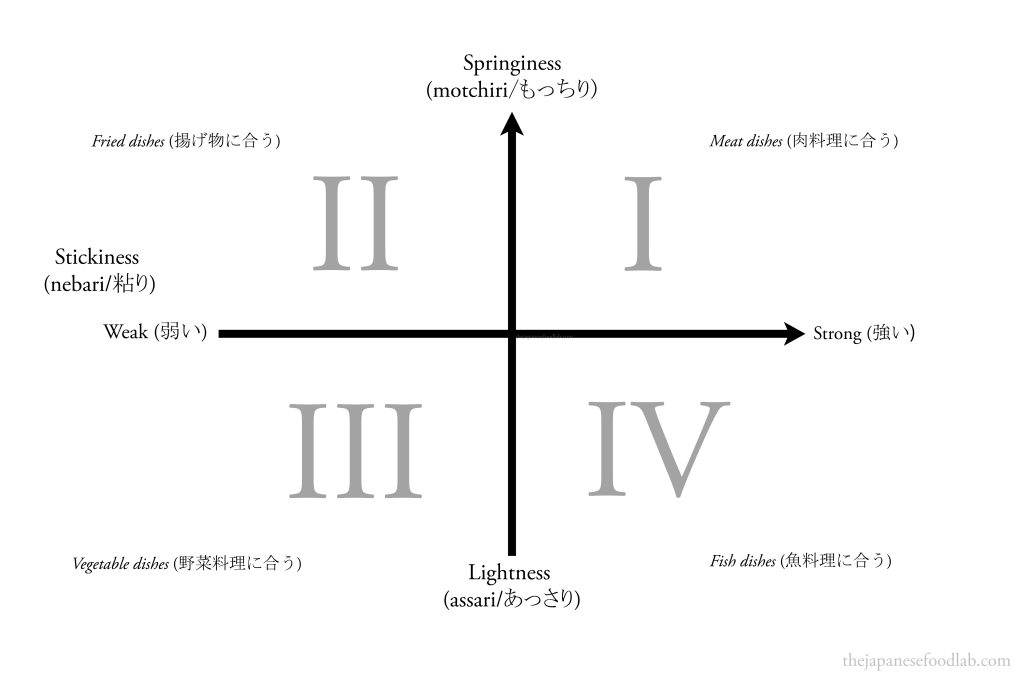

Food pairings with Japanese rice

If you can recall all the way back to the mathematics you learned in highschool, you might remember that the cartesian plane can be split into four sections called quadrants. The same goes for rice selection charts, and each quadrant actually denotes what kind of food pairs best with the qualities of that rice.

The generally accepted convention is that:

- Quadrant I is more suitable for meat dishes (肉料理に合う)

- Quadrant II is more suitable for fried dishes (揚げ物に合う)

- Quadrant III is more suitable for vegetable dishes (野菜料理に合う)

- Quadrant IV is more suitable for fish dishes (魚料理に合う)

The rice selection chart that we use

Each variety of rice that we elaborate on in their individual articles should be accompanied by a rice selection chart. The decision of where we plotted each variety on the chart was done with a blind taste test of multiple batches, followed by taking into consideration the information already available.