Miso is a fermented paste typically made with 3 basic ingredients:

- a protein source,

- Koji, which consists of the fungus Aspergillus oryzae grown on a carbohydrate substrate,

- and salt

For traditional Japanese miso, soybeans are almost exclusively used as the protein source, with rice or barley being used as the main carbohydrate substrates to grow Aspergillus to make koji. As Japan lacks salt lakes and mines, their main source of salt was seasalt. To find more information on growing koji and the science behind it, click here.

When Aspergillus oryzae is grown on rice or barley to make koji, it produces two main enzymes, protease and amylase which break down protein and starch respectively. Put simply, proteins and starches are made from long chains of amino acids and sugars. The enzymes act on these chains by snipping them up into many shorter segments which alter their taste. This is why cooked rice tastes plain as it’s made from long strands of starch, whilst cooked rice that has been cultivated with Aspergillus tastes sweet as the starch has been broken down with sugar. When this koji is mixed with a protein source, (soybeans traditionally), we are utilising the same enzymes made by the Aspergillus fungus to digest the soybean proteins. As these long chain proteins are snipped into all sorts of segments over time, the miso gradually develops its characteristic savoury and umami notes.

Salt is added to the mixture not only as a flavour enhancer, but as a preservative, allowing the enzymes to continue working away without the mixture going bad, thus allowing the taste of the miso to develop over time. Finally, a small amount of mixing liquid is added to the miso to bind it all together and adjust the consistency and texture. The mixing liquid used is usually either water, or the leftover liquid from the cooked soybeans.

This is why miso can actually be considered a two step fermentation. The first step being the production of enzymes through the growing of aspergillus on rice or barley, before then using those enzymes to transform the proteins in soybeans in a paste of umami, complimented by the slight sweetness of the koji and balanced out by salt. This in essence, is the delicious paste we call miso.

Types of traditional Japanese miso

To have a greater insight on this section, we recommend reading the science of making miso first.

There are almost an endless amount of different types of misos made in Japan, including countless regional variations and specifics which we’ll never be able to cover in full here. Instead, what we wanted to do was to give you an overview of the general styles of misos you’ll find around Japan. This range of misos obtain their unique flavour profile due to the following four main factors:

- Whether the koji is grown on rice or barley

- the soybean to koji ratio

- the amount of salt as a percentage of total miso weight

- the duration of ageing

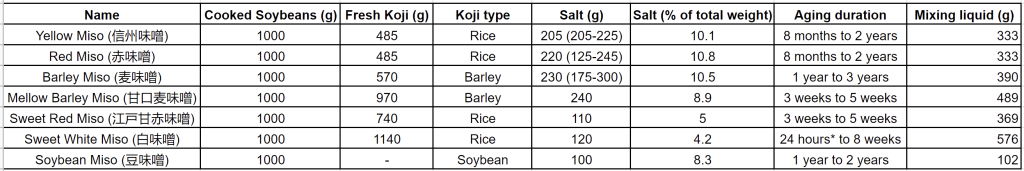

This is more clearly demonstrated in the table below, where we have deliberately standardised the weight of cooked soybeans used in the miso as 1kg so the variations in the amount of salt and koji is highlighted. For more specific weights and amounts of each ingredient, please refer to individual recipes.

To maintain the accuracy and consistency between the recipes for all the general styles of miso shown here, the weight of koji here refers to freshly made (non-dehydrated) koji. When a range of salt is given, it indicates different salt contents found around the country for that specific style of miso. The higher the salt content, the longer the ageing duration.

From the table, a clear trend you can see is that sweet miso such as sweet red and white miso, as well as mellow barley miso, have the highest koji to soybean ratio added to them. This is because their sweetness comes from the breakdown of starches into sugars in the koji as soybeans contain mostly protein. They also have the lowest salt contents, as they’re designed for quick ageing. Sweet miso, especially sweet white miso has been, and still is predominantly produced in Kyoto and has been associated with the upper class.

In contrast, misos intended for long term ageing to develop deep savoury notes have a high salt content and generally a lower koji to soybean. This is because you want a higher percentage of proteins from the soybeans that starch from the koji in your miso, therefore allowing the flavour from the fermentation to mainly come from the breakdown of proteins into amino acids. These miso styles tend to be made in places with a strong emphasis on food production such as in farming, fishing or hunting communities.

Barley miso can be found throughout Japan but is still the most popular in Kyushu. It’s an interesting example to point out as at its highest salt content of 300g per 1kg of cooked soybeans, it is a whooping 13.3% salt. At such a high salt percentage, it’s designed to be at its peak flavour after 2 or 3 years of fermentation. Mellow barley miso in turn, whilst not strictly a sweet miso, is called amakuchi mugi miso (甘口麦味噌) in Japanese. The characters for amakuchi (甘口), translates to mild or mellow, whilst the character ama (甘) means sweet. It is typically used to describe a sweetness between neutral and sweet, a sort of semi-sweet.

How miso was made traditionally

Looking at the story of miso and soy sauce, both of these household staples were originally made in huge Japanese cedar vats known as kioke (木桶). Instead of metal hoops which you’d usually find on wine or whiskey barrels, they instead had bamboo hoops specially woven to make the barrels water tight. The trays used to grow koji, known as a koji buta (麹蓋), were also made from cedar, as were the other tools used in the manufacturing process. As batch after batch of miso were fermented and allowed to age in these vats and barrels over the years, arguably the most defining part of traditional miso making was beginning to take shape, which was the establishment of a stable microbial ecosystem. As the liquid from the miso slowly seeped into the gaps in the wood, so did the myriad of microorganisms living and growing in the miso. Colonies of these microorganisms started to form and live inside the cedar wood, the surrounding air and even the building that housed the fermentation vats. Even more striking was that each and every miso-maker had their own unique microbial ecosystem which was influenced by the multitude of varying environmental factors in each location. From slight variations in temperature, weather and humidity all the way to the transfer of microorganisms from the makers hands themselves. This meant that each and every miso maker produced a miso with its own unique taste and aroma, akin to wine’s terroir.

Once the miso was made and packed into the wooden vats and barrels, it was then left to time to work its magic. There was very little in the way of climate control back then, with the fermentation ramping up as the temperature rose during the summer, caused by the increase in microbial activity, before waning and the colder months set in. With so many factors in play, no two barrels or batches of miso were ever identical, each telling its own unique story.

Back then, wood was simply used for everything as it was the easiest material to access that was durable, strong and light. Unbeknown to them at the time, wood would play a critical role in making this possible. When making miso myself, I’m always gently surprised at the variations in taste and aroma. Even within the same batch, it’s as though each barrel has its own distinctive personality, producing slight but profound differences.

The problem of modern miso making techniques

As Japan modernised, so did the manufacturing process of goods and food in an effort to lower costs and reduce safety hazards, whilst also increasing efficiency and output volume. Unfortunately, fermenting in wooden barrels and vats were seen unfavourably compared to metal tanks as metal tanks were not only stronger, but far easier to clean. It was also easier to control the temperature of a metal tank whilst also requiring a lot less maintenance compared to wood. Worse still, when metal first started being used, it was seen as far more hygienic compared to wood as it didn’t have mould growing on the outsides compared to wooden fermentation vessels which sometimes had mould on their surface, sometimes even between the hoops. While we now know that it is this unique community of different microorganisms that have taken up inside the wooden fermentation vessels that give each producer their unique flavours, back then it was just seen as unhygienic. Instead, what happened was that producers found that the flavour of their miso was very one-dimensional and that it was harder to differentiate their product from other producers.

Furthermore, the invention of temperature controlled fermentation tanks also allowed an increase in product turn-over time as the miso could be fermented at an optimal temperature all year round, producing a ready to sell product in a much shorter time. However, similar to how wine aged slowly overtime develops complexity and depth that cannot otherwise be achieved, producers soon realised that miso that was fermented at a quick paste did not have the same profile that miso that had been allowed to ferment naturally through the passage of time.

How do the miso recipes here differ from miso made in western restaurants today?

The philosophy of what constitutes good miso vastly differs between modern day miso producers and traditional miso producers. The flavour profile that most of these traditional ferments aim for is a deep nutty or almost earthy savoury flavour. This is in contrast to most other miso made by restaurants outside Japan nowadays which aim to create a flavour profile that’s fresher with greater emphasis on complex fermented notes through shorter fermentation times.

This is best illustrated from the perspective of how much salt is added to the different misos. When a high percentage of salt is added to miso, the high salinity of the miso slows down or almost fully inhibits the growth of any fungi or bacteria. Whilst this is useful as it prevents the miso from growing mould and going bad, it also inhibits useful microorganisms such as yeast and lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria. As such, most modern producers have gone in the direction of lowering the overall salt content of their miso. Taking the Noma guide to fermentation as an example, they’ve opted for 4% salt as the ideal weight for the misos they make. This is significantly lower than the average Japanese miso as their miso are designed to emphasise the complexity in taste generated by the community of useful microorganisms that live in the miso. Because of the trend towards lower salt content, most misos made by western restaurants only require 3 to 5 months ageing before their flavour reaches its peak. If left to age for longer, the miso may start to taste unbalanced or risk going bad from the growth of unwanted microorganisms.

If we were to look at traditional Japanese misos in comparison, you’d notice that all non-sweet misos have a natural fermentation and ageing time of 8 months up to 3 years. These longer ageing times are only possible due to the much higher salt content. The best example of this is barley miso, which has the potential to only reach its prime after 2 years of ageing if made with 11% salt, almost triple that of what was recommended in Noma’s book. If made with 13.5% salt, it then reaches its prime after 3 whole years of fermentation. Whilst such a high salinity inhibits the growth of helpful microorganisms, what you get in return is a product that will get better with time through the slow work of the enzymes produced by the koji. This is the kind of miso that we’ll be focusing on here for this series.

What time of the year was miso traditionally made?

Miso in Japan was traditionally made during the colder months, anywhere from late autumn to early spring. This was because there tended to be less bacterial and fungal activity due to the low temperature, thus reducing the risk of the miso being infected by unwanted microorganisms. In our opinion, it’s also much easier to naturally cool down the soybeans after cooking during the cold, as otherwise there’s a risk of the soybeans fermenting into natto when making large batches. Our personal preference is actually to make miso during late autumn as it allows us to take advantage of the year’s new crop of harvest rice (新米) and soybeans (新豆). The miso can then slowly stabilise during the winter before its fermentation ramps up during the spring and peaks in the summer. Nowadays, only traditional producers follow this tradition as large manufacturers use temperature control fermentation tanks or environments anyway, doing away with the fluctuations in seasonal temperature.

Restaurants outside Japan that make miso have no regard to the time of the year when making miso, as their main concern is simply making miso in time to meet the customer’s demand. With the rise of temperature controlled fermentation, there’s no strict reason or benefit to adhering to the time of the year when miso is made, but I do know of some traditionalist who don’t approve of how miso is made all year around as it diminishes the concept of cultural activities being tied to seasonality.

Thank you so much! I am truly grateful for this wealth of knowledge! Such a wonderful help.