This article is part of our series on making tempura.

Typically after work at the sushi restaurant I would be so tired that I’d either just wolf down a tamago kake-gohan at the restaurant or grab a sandwich or onigiri from the seven eleven before taking the train home. However, once in a while I would meet up with my friend (shoutout to Kenji!) to go eat at our favourite tempura restaurant. I can’t even remember how we found it at this point, maybe it was a recommendation by someone, but it was cool in the way that it was hidden 3 floors underground in a little corner making it almost impossible to find if you didn’t know it was there.

This tempura restaurant was something like a hybrid restaurant between high-end tempura establishments and your everyday tendon restaurant. Instead of cooking the tempura in the back kitchen and serving it out on a plate, the layout of the restaurant was a large rectangle with 2 tempura stations situated in the middle and all the customers seated around the rectangle. Rather than paying 30 000 yen for a meal here, you’d only pay 1000 yen for a set that included tempura, rice, miso soup, dipping sauce with grated daikon, 3 kinds of salt, and unlimited sides of the day such as salted squid or simmered pumpkin.

Everything in the restaurant was designed around a fast food concept, the rice came from a machine and you had to get your own water or tea from a cooler. However, the star of the show was definitely the tempura, which was cooked in front of you at the tempura station you were facing and served straight to you just like one of the high-end michelin restaurants. The floor plan was very no-nonsense, with drains surrounding the tempura stations to allow for easy cleaning and pots of oil around the floor. But somehow, this place’s tempura was the best I’d ever eaten to date, and it was just addicting. Heck I even dragged Esme (who used to contribute to this site) to the restaurant just to figure out what was up. After going there many, many times, the factor that ultimately kept us coming back was not how crisp the tempura was, but how crisp the tempura piece stayed even after letting it sit for long periods of time. Turns out, the way in which tempura is served has a large impact on the final quality.

Why does my tempura go soggy?

Nathan Myhrvold’s modernist cuisine doesn’t say much on tempura, but does go in depth on the science behind deep frying and it’s actually the same explanation that tells us how to make great tempura. When you deep fry a piece of food, the bubbling of the food in the oil is actually the water from the food boiling. As the entire piece of food is submerged in oil, the steam from the water boiling has nowhere to escape other than to leave the food through the batter in streams of bubbles. It is this stream of bubbles that provide outward moving propulsion, thus preventing the oil from penetrating the food and making it oily. In fact, the key insight here is that because water has a maximum temperature of 100°C, the steam trapped by the batter is actually cooking the food inside whilst the batter on the outside is being fried. This means that a perfectly deep fried piece of food is actually perfectly steamed on the inside because the temperature doesn’t exceed 100°C and perfectly fried on the outside. It is this very balance that tempura chefs strive to train for year after year. You can learn more in our article on the science of tempura frying oil.

If you over deep fry a piece of food it becomes oily because the water within the food has now all evaporated and due to the lack of outward moving bubbles, the oil can now penetrate into the food. Of course the evaporation of water doesn’t suddenly come to a halt, but slowly slows down gradually as all the water evaporates. This is why tempura chefs are able to tell the doneness of the food based on the size of the bubbles, as the bubbles gradually shrink as the amount of steam decreases.

But for the purpose of this article, it’s actually the opposite of what could happen and what happens after that matters most to us. If insufficient water is not cooked out of the food before it is moved from the water. Steam will continue to be emitted out of the food and absorbed into the batter, making the batter more and more soggy the longer you leave it. Therefore, the skill of making and maintaining crispy tempura ultimately comes down to how you manage steam when serving the tempura.

The optimal way to serve tempura

Any deep fried food eaten right away will yield extremely crispy results. The problem arises when you either let it sit for a while because you’re busy eating something else or when you’re making multiple different types of tempura one after another and then serving them together. By the time you do all this, most likely the tempura batter would have gotten soggy as the crust absorbs steam, which leads us to rule 1: tempura should be served and eaten immediately. This is why all the high-end tempura establishments only have 7 to 10 seat bars where each piece of tempura is fried in front of the individual and then immediately served. Only after the piece is consumed does the next piece begin to be cooked.

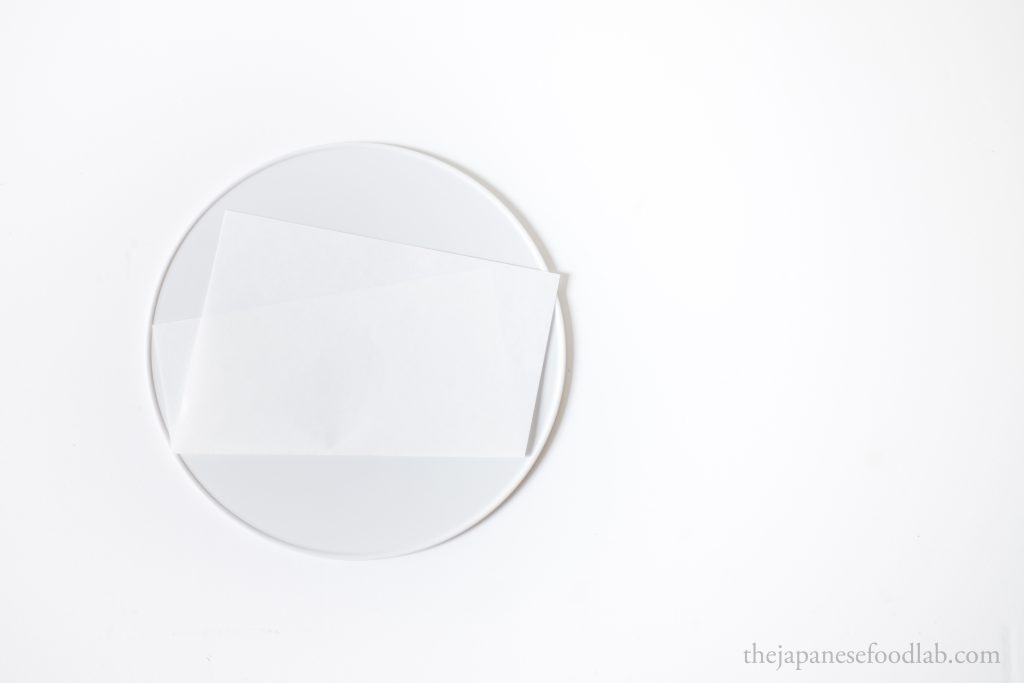

Once a piece of tempura is fried, the chef will dab it once on tempura paper on their side of the counter to remove excess oil, before placing it directly before you on another piece of tempura paper. This tempura paper, which is traditionally made with Japanese washi paper, is designed to absorb any excess oil which helps to maintain the crispness of the tempura. If serving tempura piece by piece at your kitchen bar at home, then this is a good way to go.

However, the conventions in these restaurants are not the most practical at home sometimes as by the time you have made a plate full of tempura, the pieces you had fried earlier would already start to be soggy. Even if you were to pile them on tempura paper (which you can typically buy in any cheap 100 yen store), the pieces piled on top will trap the steam being released from the pieces below, causing the pieces below to get extra soggy. This brings us to rule 2: serve in a manner that allows steam to escape. This is why at the restaurant that inspired this post, the tempura wasn’t served unto tempura paper, but onto a tray with a wire mesh cooling rack on top, the kind that you’d typically use to cool down cakes, biscuits and cookies. Even in terms of moving the tempura, the pieces were placed into a wire meshed strainer over a bowl and brought to you, before placed on your cooling rack. This cooling rack idea was ingenious as it allowed the excess steam to escape from both above and below the tempura piece, allowing it to continue staying crisp. To actually test if this was something they’d pay attention to at the restaurant, we actually waited and waited as they slowly added tempura pieces to a cooling rack in a single layer until it was full, and were delighted to see the chef add another cooling rack to our table as he didn’t want to pile tempura on top of one another. Rule 3: don’t pile up your tempura more than a single layer. I cannot emphasise enough how this small change of using a wire rack to serve tempura can have a much bigger impact on the final quality of the tempura compared to all the changes to cooking technique and ingredients you could use.

Further reading

While the information above covers the method of serving tempura that optimises for the preservation of quality, various other cooking factors ultimately affect the quality of your tempura. To learn more, browse through our extensive collection of articles on many aspects of tempura making.