Update: This article is now redundant and out of date. We’ve written a series of articles on tempura that go into far greater detail, from the science of batter to how to choose the best flour.

Typically after work at the sushi restaurant I would be so tired that I’d either just wolf down a tamago kake-gohan at the restaurant or grab a sandwich or onigiri from the seven eleven before taking the train home. However, once in a while I would meet up with my friend (shoutout to Kenji!) to go eat at our favourite tempura restaurant. I can’t even remember how we found it at this point, maybe it was a recommendation by someone, but it was cool in the way that it was hidden 3 floors underground in a little corner making it almost impossible to find if you didn’t know it was there. This tempura restaurant was something like a hybrid restaurant between high-end tempura establishments and your everyday tendon restaurant. Instead of cooking the tempura in the back kitchen and serving it out on a plate, the layout of the restaurant was a large rectangle with 2 tempura stations situated in the middle and all the customers seated around the rectangle.

Rather than paying 30 000 yen for a meal here, you’d only pay 1000 yen for a set that included tempura, rice, miso soup, dipping sauce with grated daikon, 3 kinds of salt, and unlimited sides of the day such as salted squid or simmered pumpkin. Everything in the restaurant was designed around a fast food concept, the rice came from a machine and you had to get your own water or tea from a cooler. However, the star of the show was definitely the tempura, which was cooked in front of you at the tempura station you were facing and served straight to you just like one of the high-end michelin restaurants. The floor plan was very no-nonsense, with drains surrounding the tempura stations to allow for easy cleaning and pots of oil around the floor. But somehow, this place’s tempura was the best I’d ever eaten to date, and it was just addicting. Heck I even dragged Esme (who contributes to this blog) to the restaurant just to figure out what was up. After going there many, many times, the factor that ultimately kept us coming back was not how crisp the tempura was, but how crisp the tempura piece stayed even after letting it sit for long periods of time whilst discussing the methods the chefs were using.

Google the perfect tempura and you’d find a million recipes online, including those that have dived deep into the science of the subject to figure out what’s going on. From seriouseats all the way to modernist cuisine. But whilst all of them emphasise the technique and recipe for the batter, none of them ever go in depth about how your setup and the way you serve the tempura affects the eating experience of the final product. And I’m not just talking about ambience and expensive tableware here. It’s true that you’d definitely enjoy the food served in a high-end restaurant with great company, wine and soft music playing in the background compared to the same food just served at home, but this isn’t about this stuff. It’s about how everything other than the batter, from the setup to the serving, is important for making the perfect tempura that stays crisp.

Why is my tempura not crispy?

Any deep fried food eaten right away will yield extremely crispy results. The problem arises when you either let it sit for a while because you’re busy eating something else, when you’re making multiple different types of tempura one after another and then serving them together or when you’re making it in the kitchen, plating it up and then serving it. By extending the time between frying and consumption, most likely the tempura batter would have gotten soggy by now, which leads us to rule 1: the time between frying the tempura and eating it should be minimised . This is why all the high-end tempura establishments only have 7 to 10 seat bars where each piece of tempura is fried in front of the individual and then immediately served. Only after the piece is consumed does the next piece begin to be cooked. Going back to common tempura recipes that you’d find online that only contain eggs, flour and water, these recipes just become soggy not due to the failure of the recipe, but due to the failure of how it is served. More modern recipes that use cold sparkling water, cornstarch or rice flour that contains no gluten or vodka, are able to extend the time that the tempura remains crispy between frying and serving but gradually become soggy as well if given enough time.

What’s the science behind why your tempura goes soggy?

Nathan Myhrvold’s modernist cuisine doesn’t say much on tempura, but does go in depth on the science behind deep frying and it’s actually the same explanation that tells us how to make great tempura, but first a primer on deep frying. When you deep fry a piece of food, the bubbling of the food in the oil is actually the water from the food boiling. As the entire piece of food is submerged in oil, the steam from the water boiling has nowhere to escape other than to leave the food through the batter in streams of bubbles. It is this stream of bubbles that provide outward moving propulsion, thus preventing the oil from penetrating the food and making it oily. In fact, the key insight here is that because water has a maximum temperature of 100°C, the steam trapped by the batter is actually cooking the food inside whilst the batter on the outside is being fried. This means that a perfectly deep fried piece of food is actually perfectly steamed on the inside because the temperature doesn’t exceed 100°C and perfectly fried on the outside. It is this very balance that tempura chefs strive to train for year after year.

If you over deep fry a piece of food it becomes oily because the water within the food has now all evaporated and due to the lack of outward moving bubbles, the oil can now penetrate into the food. Of course the evaporation of water doesn’t suddenly come to a halt, but slowly slows down gradually as all the water evaporates. This is why tempura chefs are able to tell the doneness of the food based on the size of the bubbles, as the bubbles gradually shrink as the amount of steam decreases.

But for the purpose of this article, it’s actually the opposite of what could happen and what happens after that matters most to us. If insufficient water is not cooked out of the food before it is removed from the oil. Steam will continue to be emitted out of the food and absorbed into the batter, making the batter more and more soggy the longer you leave it. Because of this, tempura should be served as soon as possible. This being said, it’s impossible to fry out all of the water from the food for the reasons said above, which is that it’ll cause the food to start absorbing the oil. The exceptions for these are extremely thin ingredients that themselves already hold very little water such as shiso leaves, mitsuba parsley, sakura ebi or even prawn heads.

How does the way tempura is served contribute to its quality?

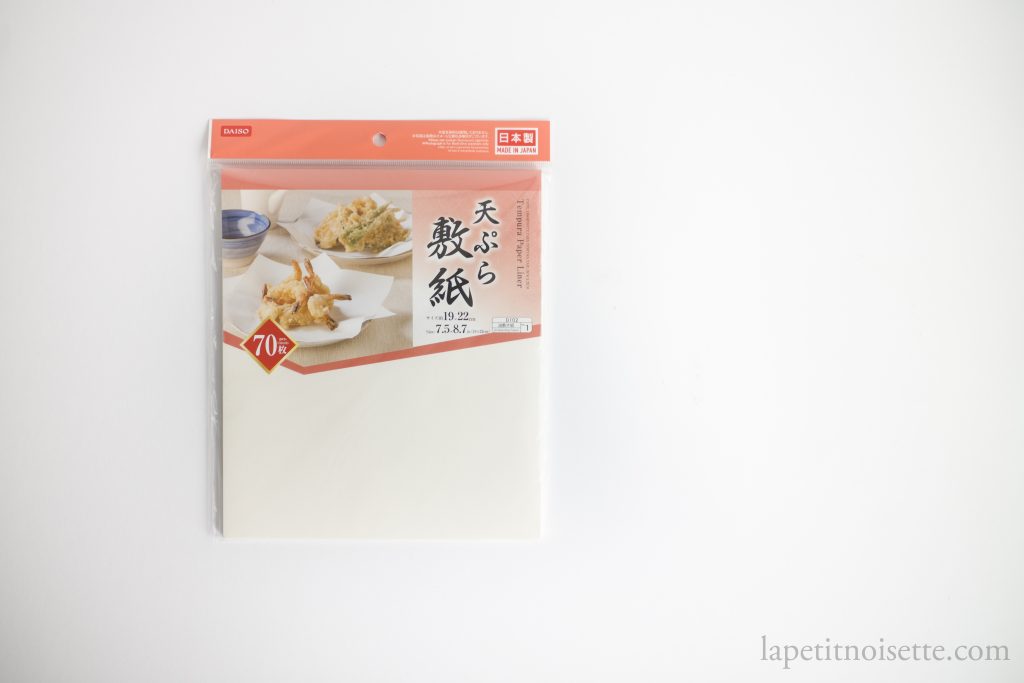

Now that we know what causes your tempura to go soggy, it’s easy to work out how the way it’s served affects its quality. Firstly, as repeated many times already, tempura should be served as soon as possible, but there are actually ways to maintain the crispness that have nothing to do with how you cook it. A traditional tempura restaurant fries the ingredient before usually dabbing it once on tempura paper on their side of the counter to remove excess oil, before placing it directly before you on another piece of tempura paper. This tempura paper, which is traditionally made with Japanese washi paper, is designed to absorb any excess oil which helps to maintain the crispness of the tempura. However, the convention in these restaurants is that the piece at hand is eaten before the next piece is fried, therefore it is actually not suitable to use in a home setting as by the time you have made a plate full of tempura, the pieces you had fried earlier would already start to be soggy. Even if you were to pile them on tempura paper (which you can typically buy in any cheap 100 yen store), the pieces piled on top will trap the steam being released from the pieces below, causing the pieces below to get extra soggy. This brings us to rule 2: serve in a manner that allows steam to escape. This is why at the restaurant that inspired this post, the tempura wasn’t served unto tempura paper, but onto a tray with a wire mesh cooling rack on top, the kind that you’d typically use to cool down cakes, biscuits and cookies. Even in terms of moving the tempura, the pieces were placed into a wire meshed strainer over a bowl and brought to you, before placed on your cooling rack.

This cooling rack idea was ingenious as it allowed the excess steam to escape from both above and below the tempura piece, allowing it to continue staying crisp. To actually test if this was something they’d pay attention to at the restaurant, we actually waited and waited as they slowly added tempura pieces to a cooling rack in a single layer until it was full, and were delighted to see the chef add another cooling rack to our table as he didn’t want to pile tempura on top of one another. Rule 3: don’t pile up your tempura more than a single layer. I cannot emphasise enough how this small change of using a wire rack to serve tempura can have a much bigger impact on the final quality of the tempura compared to all the changes to cooking technique and ingredients you could use.

How does the way ingredients are prepared contribute to the crispness of the tempura?

This idea behind the excess internal steam causing the tempura to not remain crisp also informs the way we prepare the ingredients for tempura. By removing as much excess water as possible, you’re able to ensure the most shatteringly crisp tempura. Again, this section is actually nothing new and serves the purpose to emphasize parts of the tempura preparation that can be found in all recipes but are typically overlooked or not seen as crucial steps in making tempura. This process can be seen in all parts of how ingredients are traditionally prepared. For example, fish is dried using fish paper as in a sushi restaurant before frying (or if the recipe is in english it probably says blot with paper towels). A small cut is also made in the tail of the prawn before being scraped with the tip of a knife to squeeze out excess water before the entire prawn is dried with fish paper again. Even the famous uni wrapped with shiso leaves tempura incorporates this technique as both sides of the shiso leaf is dusted with flour before used to wrap the uni as the inside absorbs the water from the uni whilst the outside dusting lets the batter stick to the leaf. This leads us to rule 4: make sure your ingredients are as dry as possible before you fry them.

This has also led to more interesting ideas such as using ever so slightly under ripe eggplants for tempura as ripe eggplants tend to have soggy flesh that will steam up the batter. The most modern tempura ingredient that plays on this idea of course are courgette flowers stuffed with ricotta and parma ham. The flower petals of courgette flowers themselves contain little to no moisture and are therefore perfect for tempura. They are the perfect vessel that can be used to encapsulate ricotta cheese which will melt from their own steam. If the flowers are torn in the process and the ricotta cheese leaks out into the oil, the batter will not only not be crispy, but will cause the oil to splash.

How does the cooking setup contribute to the overall quality of the tempura?

The hardest part about deep frying at home is actually the method by which the oil is heated. Our conventional stoves or induction heating heats the pot of oil from the bottom, meaning that there is a constant convection correct of the hot oil moving towards the top whilst cool oil on top sinks to the bottom. This also means that bits of tempura flour that start to brown and absorb oil will sink to the bottom of the pot and burn as the heat source is from the bottom. In a commercial deep fryer in western restaurants and fast food chains, the heating element is actually around the size of the oil container, meaning that bits that fall to the bottom do not burn. Japanese tempura restaurants tend to use a mixture of side heating deep fryers and the pot on a gas stove setup you’ll find at home. Especially when it comes to high end ones, you’d be surprised to find that most of them still use a pot on a stove. The reason why this is alright for tempura is that compared to other types of deep fried food, the batter for tempura is not only a liquid coating, it is also extremely light, meaning that the bits that do flake off from the food tend to float on top. This lets you remove it with a sieve before they sink to the bottom. Because of this, you’d usually find the chef scooping out excess fried batter frequently between pieces of food to ensure they don’t sink to the bottom of the pot, and don’t stick to other pieces of food. Rule 5: remove extra batter from the pot between frying pieces of food.

When it comes to the type of pot used to fry tempura however, the most traditional you’d find would be a wide but not extremely deep copper pot. The reasoning behind this is that copper is the second best conductor of heat behind silver, making it the best conductor of heat for cooking. This means that you won’t have hot spots when cooking food, or when deep frying, the oil will heat up and cool down quickly, giving you the greatest amount of control over the heat. Pure copper pots are hard to find and they are traditionally lined with tin. However, nowadays it’s possible to find copper pots lined with stainless steel. The debate between stainless steel and tin is simply that tin is a better conductor than stainless steel and is also non-stick but has the danger of melting and also being scraped off, meaning that copper pots lined with tin need to be relined with tin every few decades. However, since you’re filling the entire pot with oil and heating it to a maximum temperature of 190°C to 200°C, there is no danger of the tin melting (at 230°C~) and food will almost never come in contact with the bottom of the pan, allowing the pan to last many many years longer. Because of that, I personally feel a tempura copper pot is much more worth it compared to a traditional copper pan.

Copper cookware has the most prestigious reputation in french and japanese cookware, and of course is the most expensive, but is it the best for us home-enthusiast tempura makers? If for pan frying a fish and sautee-ing vegetables I believe there is a case to argue for it, but maybe not so for tempura. We are not experts at manipulating oil temperatures up and down to suit different vegetables and meats and neither are we experts at controlling the heat from a stove. As the most common rule of thumb for tempura frying is 180°C for fish and meat and 170°C for vegetables, as home cooks, I believe the most basic skill of maintaining a constant temperature is the most important (with the help of a thermometer of course) and so using a copper pot that not only easily heats up, but cools down the fastest just makes this harder to achieve.

How about the chinese wok that is used for deep frying all over China? Again this is not the most suitable as the rounded shape causes the temperature to be a gradient that changes from the centre of the wok to the outer edges, rather than a uniform body of oil. This is alright for fried food in chinese cuisine that uses a much heavier batter but tends to fall short when making Japanese tempura due to the unevenness.

The solution here in my opinion is to use cast iron, which whilst takes a long time to heat up, stays hot for a long time and prevents the oil from dropping in temperature when adding food. This idea isn’t novel, as plenty of recipes for southern fried chicken already use an enameled coated dutch oven. At home I just use a cast iron nambu tekki nabe to do my deep frying. Whatever vessel you use, this brings us to rule 6: keep the temperature constant and high enough when frying.

A bit more on this. As mentioned above, the most common rule of thumb for tempura frying is 180°C for fish and meat in order to quickly fry them and retain their tenderness and 170°C for vegetables. Temperatures lower than this actually cause the batter to turn from crispy too hard and chewy as the batter takes much longer to dehydrate when fried. This can easily be caused if your ingredients are not at room temperature when you fry them, which is especially important given that you need your batter to be ice cold (more on this later). Furthermore, if you overcrowd the pot when frying, the sudden addition of so much food will cause the temperature of the oil to drop. As a rule of thumb, no more than 3 quarters of the surface of the pot should be covered with food when deep frying. The depth of the oil should also be more than twice the depth of the food being fried.

What oil is best for tempura?

According to Nathan Myhrvold’s modernist cuisine, the cycle of heating oil and letting it cool causes the oil particles to break down into smaller constituents, some which are flavourful and some which are unpleasant. This is why deep frying oil reused too many times can start to taste rancid as the unpleasant molecules start to build up. He also gives an argument against using fresh oil as it can be tasteless and cause the food to take longer to cook. This is because fresh oil lacks emulsifiers that are produced as the oil is used more and more and since oil and water doesn’t mix, there is very little contact between the food and the hot oil when deep frying in new oil as the food is coated in steam bubbles even though the food is submerged in oil. To remedy this, he recommends a trick of adding a tiny amount of used oil into the fresh oil as it acts as a catalyst for the new oil to break down and produce flavourful molecules. Of course whilst Nathan was completely right, he designed his writing around western deep fried foods like southern fried chicken and fish and chips, which have a different set of defining characteristics compared to tempura. Fresher oil is more ideal for tempura as we are not looking for the typical heavy caramelised flavours that you’d associate with deep fried chicken, but an extremely light fry, so I’d recommend against reusing your oil more than 2 or 3 times.

It is also extremely important to use plant based oils rather than animal fats when making tempura. Whilst using beef tallow to fry chips and duck fat to roast potatoes are undoubtedly far more superior than using vegetable oil, here we are again looking for a light delicate fry and using such animal fats will mask the flavour of your tempura. In Japan, it is possible to buy large cans of tempura oil which are much darker in colour compared to normal oil as they are less refined and contain some sesame seed oil which is a key component to tempura’s flavour. The large chain restaurants in Japan all typically use this oil, whilst high end tempura establishments use a blend of their own house-oil that contain a mix of different oils, usually 3 or 4, of the chef’s choice. However, sesame seed oil is usually the common oil to all house oil blends.

My personal go to oil to fry tempura is a mixture of rice bran oil and peanut oil with a small addition of sesame seed oil but any pure vegetable oil also works. When deep frying food for staff meals at the restaurant I worked at, we would always just use simple vegetable oil.

How does gluten, battering and the cooking process contribute to the crispness of the tempura?

Now that we’ve spent an extremely long period of time talking about the preparation and setup and serving, we can now finally delve into the cooking process.

The most important thing to keep in mind when making tempura as with making bread and ramen noodles is gluten development. The two main proteins that make up gluten are gliadin and glutenin, both which are insoluble in water. Gliadin increases the batter’s stretching and extending abilities, whilst glutenin provides elasticity and resistance to stretching. Gluten is insoluble and hydrophobic, but is able to absorb around twice its weight in water. As the gluten is hydrated, the gluten proteins start to connect to each other through disulfide and non-disulfide cross-links. Mixing the batter increases the number of cross-links formed, developing the gluten. These eventually become large networks of protein, which in turn become sheets of protein.

If too much gluten is developed, your resulting tempura will not be crispy but chewy instead due to too much protein cross-linking. This brings us to rule 7: limit gluten formation. So what’s the solution to do that?

- Add vodka to inhibit gluten formation (a seriouseats trick)

- Keep the batter cold to slow down gluten development

- Use cake flour which is 8-10% gluten compared to normal flour which is 12-14%

- Substitute some of the wheat flour with cornstarch/rice flour which are gluten free.

- Mix your batter less to cause less gluten development

- Mix your batter just before you fry it as once water is added to flour gluten development doesn’t stop even if not mixed.

Because of this last point, it’s important that the tempura batter is made just before it is used. Even in high end tempura establishments, the batter is made multiple times over the course of a meal. It’s actually by coincidence then that the use of chopsticks traditionally to mix the batter actually aids this process because chopsticks, compared to a whisk or fork, are a horrible implement for mixing together substances thus developing hardly any gluten at all.

In fact, the batter should be so lightly mixed that there are still large clumps of flour left in the batter, and can be better described as folded rather than mixed. According to Shizou Tsuki in his legendary book Japanese Cooking Made Simple, the mark of a good tempura batter is that there still remains a powdery ring of flour at the sides of the mixing bowl with lumps of flour floating on top of the bowl. In fact he talks about this part so beautifully that I’m just going to quote him here:

The very act of dipping the materials in actually completes the mixing. The morsels pass through the batter ingredients roughly in an egg-water-flour sequence, since most of the flour is still floating on the water and the egg lies at the bottom of the bowl. This rudimentary combining procedure is what “does the trick.”

If all the above is true, why not go all the way and exclude wheat flour from the equation anyway, making a batter purely from cornstarch or rice flour? This actually results in a batter that doesn’t have the same mouth shattering crispness, as it does not contain the little crispy bits sticking out on the outer coating. Instead the batter is more uniform and almost grainy. Though this is not the most accurate description. It’s hard to put it into words. The reason why is because cross linking of the gluten strands are what gives the batter strength and elasticity, thus allowing the batter to crisp up in larger flaky pieces rather than in a more powdered form. You want to limit gluten formation, not eliminate it completely.

After drying your ingredients, it is also important to coat your ingredients lightly in flour to allow the batter to coat and stick to the food. In my personal opinion, rice flour or corn starch are the most ideal for dusting the food but using normal flour at this point is alright, as long as you focus on making sure the coating is thin. This brings us to the next hallmark of good tempura, rule 8: make sure the flour coating is as thin as possible. The reason why this is possible is because it allows the resulting tempura to have many many tiny holes or gaps in the batter once fried, which are actually a way for steam to escape, preventing the batter from absorbing steam and going soggy. In a way this is similar to rule two in that it is a crucial step keeping the tempura from going soggy. Why go through all the effort to make crispy tempura but then to let it go soggy afterwards?

Once you’re ready to begin frying in a pan of hot oil, gently lower the battered ingredients into the pot of oil to prevent splashing. At this point, you can immediately sprinkle in some additional batte from your mixing bowl by either dipping your fingers into the batter and letting the batter drip into the oil, or by gently flicking your hands open over the oil to release the batter droplets into the oil. It’s important to do this right after you add in your ingredients to the pot as just before the batter becomes solid and crispy, some of the tempura batter on the food and the batter you add are still liquid enough to stick together, giving your tempura extra crispy bits on the outside. This is also useful as because these additional crispy bits attach to the tempura batter on the food, meaning that any steam that can may the tempura batter immediately enclosing the food to go soggy will not penetrate into this outer crispy bits, allowing your tempura to remain crispy just that little bit longer.

Remember to not add too much batter at this point as it will cause the temperature of the oil to suddenly drop, given that your batter is already ice cold. It will also cause a large release from steam as the water from the batter is quickly evaporated, which will scald your hand if you leave it hovering above the pot.

My ideal tempura setup

My personal ideal tempura set up is a bar seated with guests. Each guest will have a bowl of miso soup, rice and dipping sauce, and a personal wire rack over a tray. The centre of the bar will have a large pot filled with oil over a stove, a bowl with a sieve that is used to scoop out excess fried batter, a tray with potato flour or corn starch for dusting, a bowl with batter, a tray with the ingredients lined with paper towel, and a tray with tempura paper.

Perfect Crispy Tempura recipe

The recipe below is the universal one I use when frying tempura.

- 80g cake flour/low protein flour

- 80g rice flour or cornstarch

- 2 ice cubes, ~20g each totaling 40 g

- 100ml of Water (ideally ice cold and/or sparkling but if not normal water works)

- 60ml of Vodka

- 1 egg, ~50g each

To start, make the batter whilst the oil is heating up by whisking everything together with a pair of chopsticks until barely combined. Once the oil has reached the desired temperature (180°C for fish and meat and 170°C for vegetables), dust an ingredient that has previously been patted dry in rice flour, dip into the bowl of batter and add to the hot oil. Immediately sprinkle some additional batter into the oil to give the tempura an added crispiness. Once the tempura has turned a light golden colour and the steam bubbles have started to become small, remove from the oil and dab on the tempura paper to remove excess oil, before placing it on the wire rack of the guest to immediately enjoy.

Before frying the next piece of tempura, use a small sieve to remove any excess batter remaining in the oil and ensure that the oil is back up to temperature before adding in any additional pieces.

Excellent article on tempura as always. I run a Japanese restaurant and had to develop a tempura flour recipe so that any cook could deliver a consistent result. It is different from a traditional tempura restaurant but it stays crispy and it is easy to prepare: 100g all purpose flour, 100g potato starch, 100g corn starch, 15g baking powder and some msg mixed together. Usually I mix 100g of this mixture with 150g of regular water (it doesn’t even need to be cold). The result is a very thin batter that stays crispy for a long time.

Thank you for sharing your recipe! I’ll definitely try it out for myself.

Do you guys have any other platform where it would be easier to interact and would allow posting pictures, etc?

No sadly we don’t. The sushi geek website used to have a forum where people can post and comment on stuff but sadly that seems to have closed down for some reason. We do have an Instagram but that’s about it, and it’s not very active. We’ll be working to change that soon of course.

You guys write the best content on Japanese food in the English language ever!! I wish I could interact more.

Thank you! We really put in a lot of effort into what we produce. Maybe one day in the future we will have a place where people can interact more.

Surprised no one asked… so Where is that restaurant? I am a HUGE tempura fiend and always on the hunt for good tempura.

The name of the restaurant is Tempura Hirao, a chain of tempura restaurants in Fukuoka. 🙂

Excellent writing.

The most interesting and informative article I’ve ever read about tempura.

Thankyou.