Go to any famous eel establishment in Japan and order their grilled unagi over rice (鰻丼), and it’s sure to come with a bowl of soup. Unlike most bowls of soup that serve as side dishes to most Japanese dishes, this soup is not that of a cloudy miso soup, but a clear soup with a refreshing flavour. Inside the soup, you’d usually find a few mitsuba leaves floating on top with a single piece of meat floating inside that looks slightly like an oyster. To the untrained diner, this might seem like a random piece of pork or chicken that’d you find in a bowl of soup, but instead, this unassuming piece of flesh is actually the liver attached to the stomach of the eel.

Firstly, let’s clarify the terminology at play here. The japanese name for this dish is kimosui (肝吸い) which roughly translates to liver soup. In fact, look at any source in english and they’d most likely tell you that it’s soup made with the liver of the eel. However, this is not entirely accurate, the soup is in fact made from the cleaned stomach from the eel which is attached to the liver.

Interestingly enough, the name kimosui actually makes no reference to freshwater eel at all, which might indicate that it could be the liver soup from any animal. This being said, the term kimosui in japanese is so often used to describe eel liver soup that when you use the word, it’s automatically assuming you’re referring to freshwater unagi liver soup. It could also refer to salt water eel (anago) liver soup, which is far less common given the many fewer salt water eel specialty establishments that exist. Either way, the preparation method for both are interchangeable anyway.

The great fanfare around this dish is that it embodies two main culinary concepts. Firstly, that no part of an animal should be wasted so long as it’s edible. This is part of Japanese cuisine that’s so common that it’s almost taken for granted, even when much of the western world has only begun to celebrate chefs who reduce food waste in recent times. The use of beef intestines in motsunabe or the use of unlaid chicken eggs are just one of the many examples. Even when it comes to eel, the spine of freshwater eel is deep fried and eaten as a snack, the livers grilled with sweet sauce on a stick and finally the stomach being made into soup. The second concept at play here of course, is the celebration of high quality ingredients. Building on from my article on farmed vs wild freshwater eels, high quality wild caught produce is extremely prized in Japanese culture, from bear meat, matsutake mushrooms, venison and wild boar.

Whilst the majority of eel enthusiasts would agree that wild eel tastes far more superior that farmed eel, this difference is even greater when it comes to the offal of the eel just like how eating wild mallard liver is so much gamier and darker red in colour compared to eating chicken liver. In the picture below, you can see two wild eel livers vs one farmed eel liver on the left, which is pretty obvious from its larger, more uniform size and lighter colour. As with most offal, the wild eel’s offal can sometimes have a much stronger taste and depth of flavor which some might describe as more iron and game like. However, the most prized wild eels from the most pristine rivers in Japan are suppose to be different and more complex, in the same way that wild Ayu sweetfish are supposed to have a much sweeter taste that’s reminiscent of cabbage because of the diet they eat, and in the same way prized wild boar (inoshishi) in Japan does not have the same taste as wild boars caught in other countries due to their diet of nuts and wild berries.

When you look at the entry for kimosui in the Encyclopedia Nipponica (日本大百科全書) which is the Japanese equivalent of the Encyclopedia Britannica, you can find a really interesting entry by Tetsunosuke Tada (多田鉄之助), (born 1896) which was one of Japan’s most famed food critics back in the 1900s who has authored many books on Japanese cuisine. He talks about how he used to scape the stomach with his chopsticks or bite it with his front teeth first to check if there were any fish hooks accidentally left inside, but as time went on he no longer needed to worry about that as most of the eels in restaurants nowadays are farmed!

Talk about being able to go back in time and see the perspective of someone who lived through the tipping point when what the default of what you’d get in a restaurant was transitioning from wild eel to farmed eel and wild eel became a rarity. He also made a note about how this dish is sometimes made from chicken liver or chicken gizzard but that soup made from chicken liver is not called chicken kimosui (鶏の肝吸い). This is actually interesting because the words used for soup is typically supu (スープ) or shiru (汁) as in miso shiru (みそ汁). From what I can tell, the only other use for sui (吸い) in reference to soup in Japanese is in a clear meat broth dish with egg.

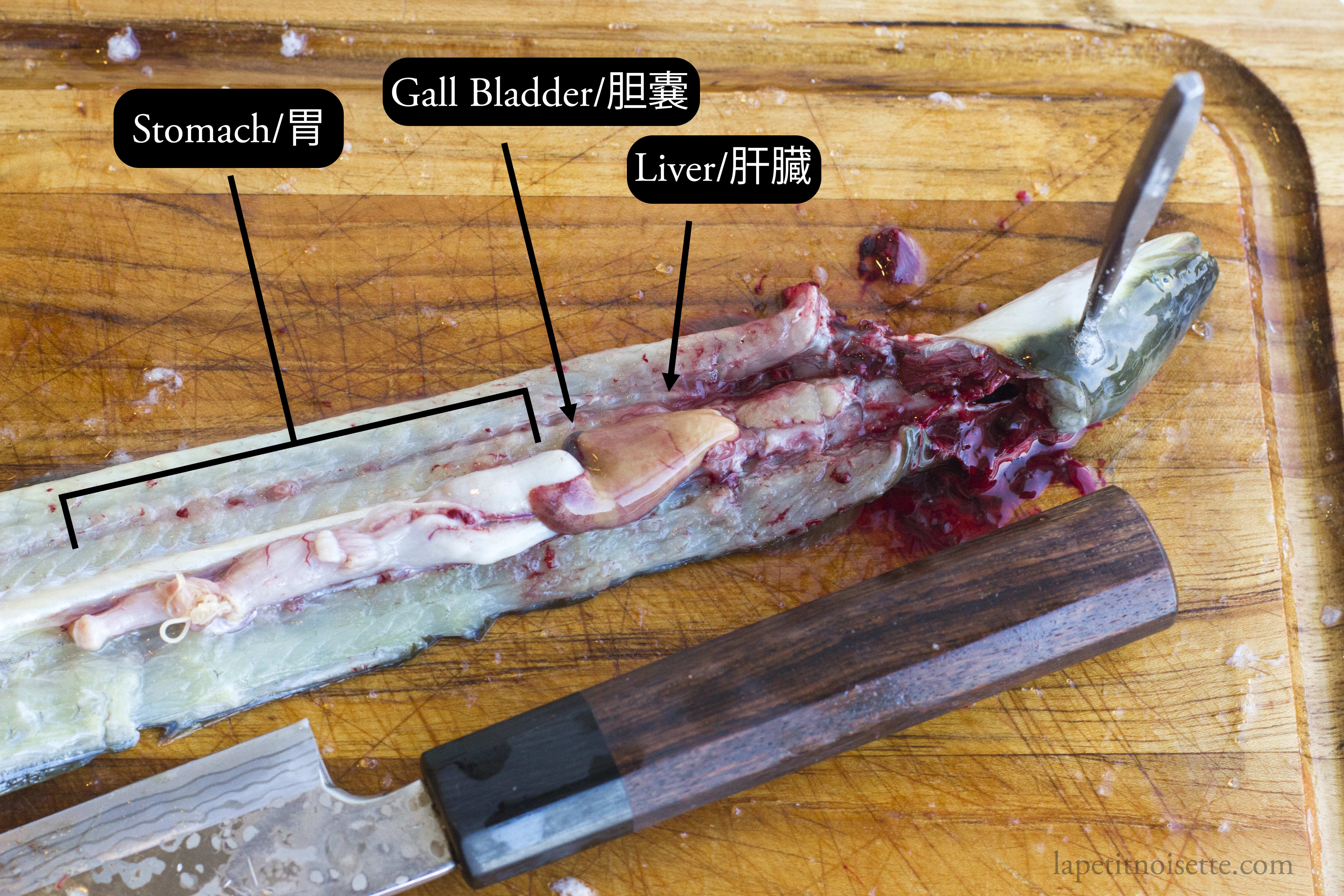

When you first cut open a live eel, you should immediately be able to identify 5 organs if you’re lucky: the heart which should still be beating, the swim bladder if you didn’t accidentally puncture it, the liver (肝臓), the stomach (胃) for the soup and the gallbladder (胆嚢) sandwiched between the liver and stomach. Occasionally you will not be able to locate the heart because it either stopped beating or was accidentally sliced into with your knife. The heart of an eel is significantly smaller than that of your usual fish so it is much harder to locate. So even if you can’t see the air bladder and heart in your eel, the remaining three organs in the list above should still be visible, which is lucky because those are the three important ones we’re going to focus on. Firstly, the gallbladder (tanno/胆嚢) or as it’s typically referred to in Japanese, the bitter jade (苦玉). True to the name, the gallbladder should be a deep green in colour, which is actually the bile produced by the liver. The bile of course, is bitter which is why the gallbladder needs to be cut out and removed. Once you cut it out, some of the bile will inevitably spill into the stomach and liver which you’ll have to wash out. You can then cut the liver and stomach out.

Kimosui Recipe (肝吸いの作り方) for 3 bowls of soup

- 3 to 6 pieces of eel liver for 1 to 2 pieces of liver per bowl of soup

- 600ml of dashi

- Salt to taste + Salt to blanch (around a generous pinch)

- 5ml of soy sauce/1 teaspoon

- 3 stalks of mitsuba parsley

- Follow the step by step instructions on how to kill and cut open an eel. Stop once the eel has been opened up (Step 6).

- Use your knife to cut under all the organs to remove them from the flesh.

- Cut off the gallbladder from the liver and stomach and discard.

- Use the back of your knife to scrape the stomach, pressing out any impurities inside.

- Wash the stomach and liver under running water to remove any bile from the gallbladder that seeped in. Be careful not to break the connection between the liver and stomach.

- Bring a small saucepan of water to boil and blanch the eel livers for 3 seconds before either transferring to an ice bath or running under cold water to quickly stop the cooking.

- Rinse the mitsuba parsley and trim the stems.

- Bring the 600ml of dashi to a boil, add the soy sauce and salt to taste.

- When the dashi is boiling, add the liver and mitsuba parsley and turn off the heat.

- Portion into 3 bowls and serve.

Notes:

- If you’re going to use the livers another day, I recommend you blanch them before storing them in the fridge for up to 2 days.