This article is part of a series on Edomae sushi.

TLDR:

- In the restaurant, we used a special Donabe claypot rice cooker from Kumoi Kiln (雲井窯) by Nakagawa Ippento (中川一辺陶先生).

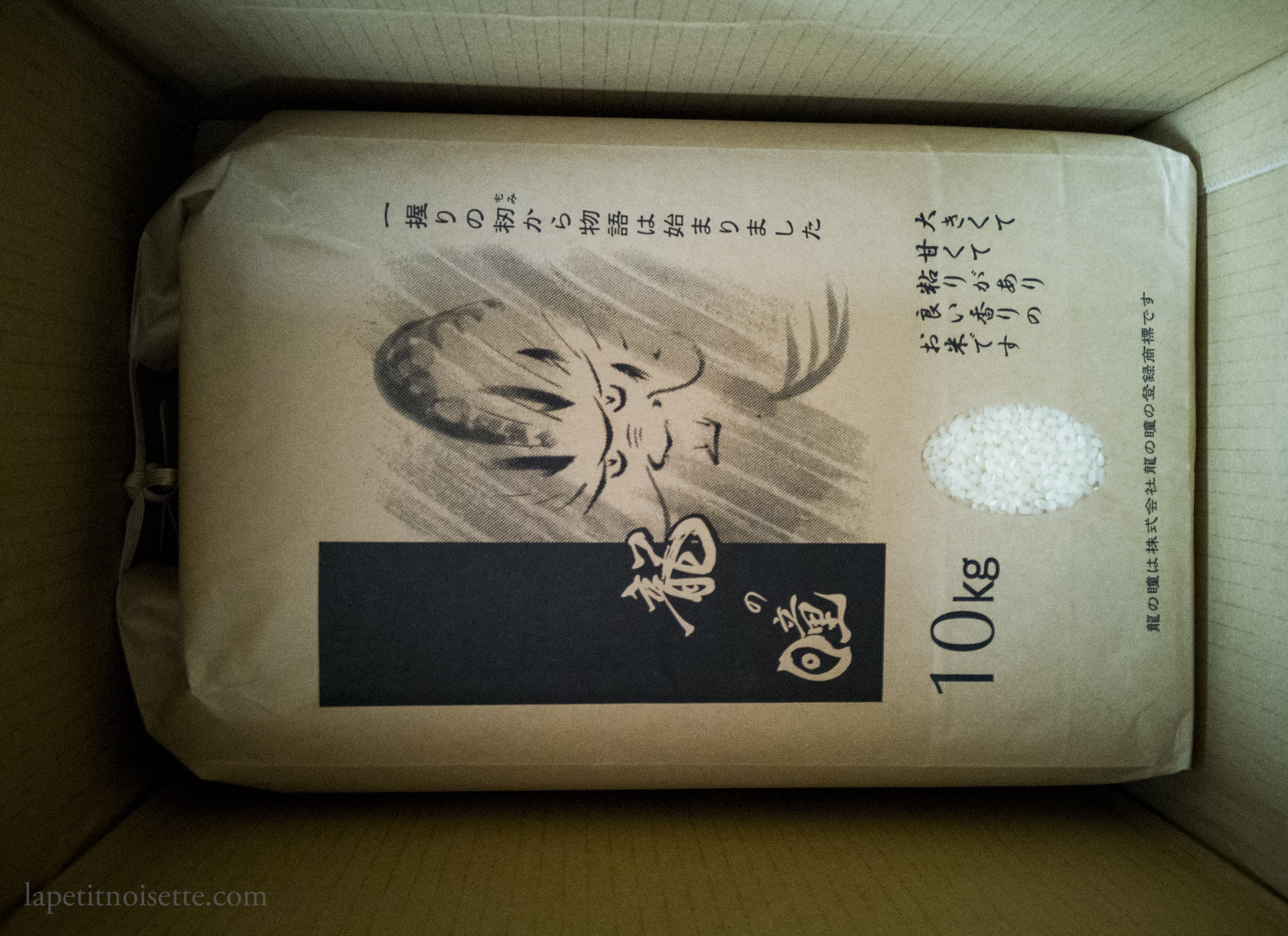

- We used a special sub-cultivar of the Koshihikari cultivar (コシヒカリ/越光) called the eye of the dragon, or Ryu no Hitomi (龍の瞳).

- The rice is then mixed with red sushi vinegar.

- Learn more about different Japanese rice varieties here.

You’ve might have heard people say that sushi is 90% about the rice and only 10% about the fish. I honestly thought this was all utter bullshit myself until I started working at the sushi restaurant. There, I realised how the rice was the most important aspect of a single piece of sushi. This was further emphasised when I started making sushi for my master to taste at the counter. When he ate the nigiri I made piece by piece, he actually flipped the nigiri upside down and ate the nigiri with the fish facing downwards, as though the rice was the star of the show, instead of the fish.

When it comes to three star Michelin sushi restaurant rice, you normally hear tales of chef’s sourcing rice from their grandfather’s field in the mountains or something along those lines. To be honestly there is a little truth in those tales but the rice made by each sushi restaurant does vary from place to place. There are however, some general guidelines that they follow explained below.

Firstly comes the cultivar of rice. Of the Japonica Species of rice grown all over Japan, the main sub-species of rice used to make nigiri sushi in high end sushi-ya’s is of the Koshihikari cultivar (コシヒカリ/越光). This cultivar of rice produces slightly firm grains when cooked which allows each grain of rice to have a gentle bite when formed into a nigiri. The name of the cultivar actually represents the old Koshi Province/Prefecture. This of course, varies from restaurant to restaurant. I personally heard that the famous Sukiyabashi Jiro does not use the Koshihikari cultivar but a different variety from the Toyama Prefecture.

So where do all the tales of sourcing rice special farms in the middle of no where come from? Each sushi master actually has his own specific sushi vinegar mix when making sushi rice. Whilst the typical mix contains rice vinegar, salt, kombu and sugar, the quantities and types of each ingredient varies. Some use red rice vinegar in the traditional Edomae-style, whilst some omit salt etc.. Therefore, each sushi master tailors the type of rice he uses to the vinegar mix he uses. In essence, the rice’s texture, sweetness and chewiness changes according to where it is grown and how mature it is allowed to grow before harvesting. In order to find the specific rice that fits the bill, many sushi restaurants results to specific supplies that grow just the right rice they want, which is typically grown in extremely small quantities.

The next comes the method of cooking. You will never find a high end sushi restaurant that cooks rice with a rice cooker. Instead, most of them can be seen using a traditional donabe rice cooker (土鍋ご飯) or a traditional iron hagama rice cooker (羽釜). I first thought that the chef’s were actually traditionalists and that modern day rice cookers could definitely make better rice that an old iron/clay pot. The most high-end of high end rice cookers can cost up to a 1000 dollars in cost, surely they make better rice? In reality, none of the above proved to be true. A high-end rice cooker can actually make rice that is just as good as that cooked in a traditional iron/clay pot. However, this is only applicable for everyday rice! If using special cultivars of rice with varying maturity to that compared to the typical rice you would get at a supermarket, a rice cooker would not be able to adapt to the difference rice and thus a traditional cooker manned by a human who can manually control and change the heat and amount of water achieves much better results.

The differences between a traditional Donabe rice cooker (土鍋ご飯) and a traditional iron Hagama rice cooker (羽釜)

The traditional iron Hagama rice cookers typically have a very heavy lid. This heavy lid keeps the steam in when cooking the rice, thus increasing the overall pressure inside the pot. The higher the pressure, the higher the boiling point, allowing the rice to cook at a higher temperature without boiling. This has the effect of producing more fluffy rice (so I am told), compared to rice cooked at a lower temperature. Some restaurants even add a pot of water or extra weight onto the lid of the Hagama rice cooker to increase further increase the pressure containing capabilities of the rice cooker (though I’m not sure how effective this is).

A donabe cooker instead, has a hole on the top, which ventilates excess steam. High quality donabe cookers are made from clay that contains a lot of microscopic organic matter. When baked at high temperature, the organic matter burns and leaves behind air pockets, which provide the donabe with unmatched insulating and heat retention qualities (think about how bad a heat conductor air is). This, added with the rounded shape of the donabe, allows it to heat evenly whilst encouraging steam to circulate whilst the rice is cooking. Some donabe even come with a second inner lid to increase heat retention. Both types of rice cookers are unique in their own way and it is up to each restaurant to decide what they prefer.

The Koshihikari cultivar (Right) vs the Ryu no Hitomi (龍の瞳) sub-cultivar of rice (Left)

At the restaurant I worked at, we used a special sub-cultivar of the Koshihikari cultivar called the eye of the dragon, or Ryu no Hitomi (龍の瞳). The company that grows this rice apparently ran a DNA test on this cultivar. Due to an unidentified genetic mutation, this specific sub-cultivar has rice grains that are 1.5 times larger compared to normal rice grains, which contributes to a sweeter and stickier quality due to their high starch content. On top of that, the rice is also harvested at a later maturity, allowing it to reach maximum size.

The company also specifically states that they are Organic JAS Rice certified, meaning that they only use organic fertilisers, with the rice being non-genetically modified.

How we cooked rice in the restaurant

We never washed the rice clean but always washed the rice until the water was still slightly milky. The excess starched left behind made the rice taste slightly sweeter. In any other restaurant, the rice is washed until the water runs cleaned to remove any excess starch. After washing, we then varied the amount of water used to cook the rice. At our restaurant, this actually depending on the time of the year. For example, for 3 cups of rice, we would used 2.8 cups of water to cook the rice. For rice 5 to 8 months old, we would use 3 cups of water and for rice 8 months old and above, we would use 3.1 cups of water.

The water used is also not tap water, but filtered water that we either buy in bottles from a supplier, or obtain from a water filter. (Just use supermarket bottled water)

The next step was soaking the rice in order to reduce cooking time. The rice was soaked in the water that was going to be used to cook the rice. This also depending on the time of the year. Immediately after rice harvest, freshly delivered and milled rice did not need to be soaked before cooking. However, 5-8 months later, the rice needs to be soaked for 3 minutes. More than 8 months after harvest, the rice should be soaked for 10 minutes before cooking. The soaking works mainly to reduce the actually cooking time needed whilst encouraging even cooking of the rice. We soaked the rice directly in the claypot.

In the restaurant, we used a special Donabe claypot rice cooker from Kumoi Kiln (雲井窯) by Nakagawa Ippento (中川一辺陶先生). The instructions to cook rice in these pots slightly differ compared to other donabe rice cookers. After lightly washing with only water, the claypot is ready to be used. Cook the rice on high heat until the water is boiling (around 10 minutes). The water is boiling when steam can be seen escaping from the lid of the pot. It is natural for water to start bubbling from the sides of the lid of the pot. Once boiling, turn down the heat to low and cook for 10 minutes, before allowing the rice to rest for 10 more minutes with the lid on. The residual heat of the pot will be enough to finish cooking the rice. Due to the thickness of the clay as well as the full glaze, high heat can be applied to the pot immediately without it cracking. After turning off the heat, we actually carry the pot out to the counter to continue cooking in front of the guest before mixing with sushi rice.

If using a normal Donabe rice cooker, or the famous Kamado-san Iga Donabe rice cooker, cooked the rice over a stove top for 13-15 minutes before turning off the heat. Puffs of steam would appear above the Donabe pot a few minutes before the rice was done. Turn off the heat and allow to continue cooking for 20 minutes.

Only the top of the rice was scooped out and used to make nigiri. The browned crusted rice at the bottom was not served to the guest, but was however eaten by the staff at the back. This part is actually the tastiest part of the meal!

In order to prevent the rice at the bottom from crusting or burning however, we sometimes used a rice net as shown in the picture below.

When we had excess rice left over after service, we always wrapped the rice in clingfilm and stored it at room temperature in contrast to storing it a rice warmer. This variety of rice tended to become sticky after storing in a rice cooker.

*For a service of 10 people over 3 hours, we cooked rice twice to ensure that the guest always eat fresh rice. We do not cook rice in one single go.

After cooking, the rice is then mixed with sushi vinegar.

[…] source : La Petit Noisette […]

Hi there, thank you for this blog, the information is priceless and incredibly insightful! I just have a couple of queries regarding soaking the rice. If pre- soaking, would you soak the rice in the water it will cook in. Or soak, drain, then combine. Also, once the rice is soaked does this change how much water it should cook in? So older rice requiring longer soaks would cook in less water? Thank you for your time, Joseph

We’d soak the rice in the water it’d cook in. After we add the initial amount of water we don’t add anymore.